Virtual justice – where do we go from here?

Dan Bindman explores the impact of the pandemic on the courts and asks whether virtual justice is here to stay

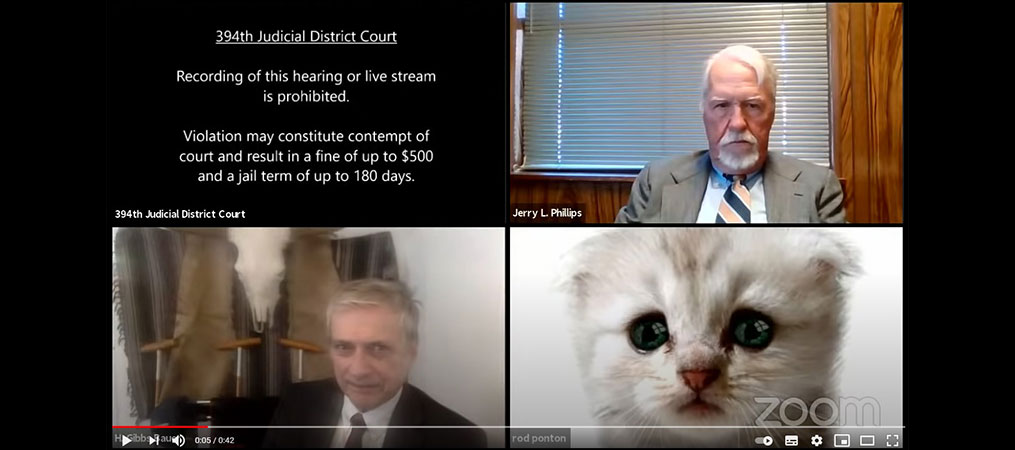

In these grim times, it took a lawyer inadvertently appearing in court as a cat to cheer up the world. American Rod Ponton found himself the focus of gentle global ridicule after he appeared on Zoom for a Texas fraud case wearing a digital kitten mask while using a borrowed computer. The cat’s mouth moved pleasingly in sync with his voice.

Luckily Mr Ponton took it in good humour, as did Judge Roy Ferguson, who later said the attorney showed “incredible grace” as the story went viral on social media. The judge had actually tweeted out the video, with the caption: “Important Zoom tip: If a child used your computer, before you join a virtual hearing check the Zoom Video Options to be sure filters are off. This kitten just made a formal announcement on a case in the 394th (sound on).”

These little snafus were bound to happen during a year when the world has seen the accelerated adoption of videoconferencing technology that could never have been predicted, but has amounted to a concentrated experiment of how well it works in a range of commercial and social settings.

Some justice systems have been able to operate relatively smoothly despite the dangers of face-to-face Covid-19 transmission, due to the possibilities offered by low-cost, universal remote working. Clients, lawyers, and judges have all had easy access to the technology from their home computer desktops, whereas only a few short years ago this would have been impossible.

Its adoption by courts in England and Wales was made simpler by the fact that a project to introduce video had already been ongoing for a number of years. It is undeniable that the struggle HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) might otherwise have had to achieve its acceptance has been greatly eased by necessity, as the technology was forced on the country by the pandemic.

Of course, the learning curve has been steep and the process sometimes tricky for many technophobes in the legal profession, as with the general population. Aside from the cat lawyer, there have been various examples of people using Zoom or Microsoft Teams and forgetting that cameras were still broadcasting live in their homes.

Instances of people being in various states of undress, on the toilet, drinking alcohol, even a Peruvian lawyer engaging in sexual relations while appearing in formal legal meetings have made headlines. Somewhat closer to home, a High Court hearing was interrupted by a troublemaker who managed to share their screen and project pornography to all those watching, while people made firework noises, blew raspberries and imitated one of the barrister’s Scottish accent.

Nonetheless, England and Wales seems to have learned the lessons at a speed HMCTS could only have dreamt of when it first embarked on its digital courts programme several years ago.

A system changed forever

It is already clear that the civil justice system in some respects has changed forever. There is apparent consensus that at least some of the simplest hearings will from now on always be done remotely, such as interlocutory applications that were previously made in person, involving expensive court time and often long journeys by clients and lawyers that have arguably been proven unnecessary.

There is apparent consensus that at least some of the simplest hearings will from now on always be done remotely

Last October, the president of the family division, Sir Andrew McFarlane, reflecting on the previous six months at a Resolution conference, said family courts had adapted so well to remote working that they had in some courts removed the historic backlog of cases altogether.

Yet HMCTS figures announced in December have suggested this performance does not extend across all civil cases. Delays in small claims reaching trial in particular were evident, they suggested.

Record redundancies have also led to enormous pressure on employment tribunals. HMCTS data showed in November that employment claims had increased by more than a third since the pandemic began, with some more complex cases being listed for 2022.

In both criminal and family law, it has been suggested that some hearings may be too serious, or personal, to be held remotely if justice is to be had and seen to be had. For instance, when parents are to be denied access to their children, or individuals will lose their liberty, some senior professionals agree that video appearances at a distance are inappropriate.

A High Court family judge, Mr Justice Francis, observed recently: “I’m dealing with the rape and murder of children and I don’t find it very nice having it in my front room or in my bedroom, or wherever it may be.”

But he acknowledged that initial appointments, directions hearings and case management hearings were well suited to being held remotely.

A fair and just process?

Fellow Emma Hicks, a senior prosecutor who previously worked as a criminal defence advocate in cases in all courts, including murder, and is now based at Cheshire police, agrees that straightforward hearings “fit in for most people better than, for example, travelling to a court centre, sometimes in another area, and needing to take time off work and so on”.

Sharing his fear that video might become the norm in too many cases, Sir Andrew agreed that while digital consent orders were being turned round much faster than before, he would “fight any suggestion” that family cases should remain online post-pandemic.

He cited research results from the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory that four in 10 parents did not understand the remote hearings they had been involved in and two thirds believed the case had not been dealt with well.

However, lawyers tended to disagree, with almost 80% feeling that fairness and justice had been achieved most all of the time.

Too late to turn back the clock

Personal injury (PI) is one area that has taken well to remote hearings generally.

One experienced PI Fellow, Craig Budsworth, legal director of his firm’s credit hire department, is frank in saying that he fears a desire to return to the past – that is, “judges wanting to turn the clock back” to in-person hearings because they missed having people in front of them when they make decisions.

But this is only a “gut feeling” and not based on conversations. “Hopefully I will be proved wrong,” he says.

Most of his hearings are quantum disputes and so fall into the ‘straightforward case’ category eminently suitable for video.

Meanwhile, clients “loved” video hearings, he reports, much preferring to log in from home “rather than having to take time out of their day to go to court hearing”.

Before the pandemic, cases were often listed, for instance, for between 10am and 2pm, but the hearing may not have actually started until 1pm and was often stayed.

In fact, the number of cases being stayed on the day of the hearing had become “unbearable” and the cost of having to keep barristers ready had risen to “astronomical levels”, he recounts.

PI lawyers were also keen on remote hearings, both barristers and those who instructed them, he adds. What used to be settlements of cases on the court steps were now settlement discussions by email.

“I think very few small claims in our world – in the litigation world – couldn’t go through this virtual platform in the future.”

High-value cases will go back to in-person hearings

Mr Budsworth praises HMCTS for ending the unsustainable situation where so many cases were stayed, and for somehow being able to implement start times for hearings with few interruptions: “I think that’s a massive step forward in comparison to where it was pre-Covid.”

In criminal law, Ms Hicks agrees that clients are very satisfied with remote hearings, although she acknowledges she has no experience of remote trials. “As a prosecutor I have not come across anyone unhappy with remote hearings, in fact probably the opposite,” she said.

Another Fellow doing regular virtual civil cases since the arrival of Covid is Ian Herbert. Video hearings are “absolutely fine” for straightforward hearings like interim applications, he says, but he is less sure about high-value cases.

This view aligns with a June 2020 Civil Justice Council survey, which found that while there was support for the continuation of preliminary matters, interlocutory hearings, and trials without evidence being dealt with by video technology, almost all lawyers agreed that high-value trials should continue to be heard in person.

The survey also raised a number of concerns about whether the pandemic has reduced access to justice to the detriment of people on low incomes the same time as legal need had risen, and that a stay on possession proceedings aiming to protect people from becoming homeless was storing up problems down the road.

The leader of the research, legal academic Dr Natalie Byrom, argued that HMCTS was not gathering enough data to ensure remote hearings were properly evaluated.

Losing the eye-roll test

Mr Herbert appreciates that remote hearings are likely to be with the legal profession for the foreseeable future, but sees some downsides.

Some parties communicate through WhatsApp during hearings

While some lawyers report using encrypted WhatsApp groups to speak to clients during hearings, others do not want to reveal their mobile numbers. Mr Herbert says he has no problem with giving clients and witnesses his number, but he understands people who do.

So far, however, he has relied on text messages; while he toyed with concurrent video hearing calls, he decided against this, given the perceived security risk.

The main difficulty with digital hearings is presenting witnesses to the court, because it is not always possible to see what traction the testimony is achieving with the judge and whether he or she Is “rolling their eyes” as the witness speaks.

There are also problems with big digital bundles, especially in the county court. Judges don’t like them and, unlike the High Court, there is no standardised system for transmitting large electronic documents.

Overall, however, clients are happy enough with virtual hearings, in his experience. “They are pleased not to have to go to court, frankly. You don’t have the intimidation factor that is associated with being in a courtroom. They can sit in the comfort of their own home.”

Serious criminal cases are generally seen as less appropriate for remote video hearings, particularly when juries are involved and benefit from seeing the body language of defendants and witnesses in coming to a rounded decision. Even before the pandemic there was profound doubt raised about video evidence given by defendants, the implication being that they were harmed by appearing at a distance.

Negative impact on incomes and training

From the lawyers’ perspective, there has been much anguish expressed over the effects of cancelling in-person trials since the pandemic was declared, not least due to the negative impact on advocates’ incomes and the training of young barristers.

This exacerbated existing trial backlogs. The government responded with a plan to extend the hours of criminal courts to compensate. It has since rowed back from this position after widespread fury among lawyers and in the face of a legal challenge from the Criminal Bar Association.

The survey also raised a number of concerns about whether the pandemic has reduced access to justice

Much time and money has been spent adapting courtrooms for safe use in large multi-handed trials. Seventy had been done out of a total estate of about 500 courtrooms by early 2021. Nearly 300 were already available for socially-distanced Crown Court jury trials, plus 17 pop-up ‘Nightingale’ courts. But the Criminal Bar Association estimated 400 usable courtrooms were necessary to make inroads into the backlog.

The lessons learned from the justice system for over a year of being forced by the pandemic to socially distance will no doubt be fought over by those with the greatest interest in maintaining or reversing the new status quo. To save money, HMCTS and the government will no doubt seek to set changes in stone where in some cases the legal profession believe they should revert to the old way of doing things.

The lower costs that result from the adoption of a chunk of hearings being done more efficiently will doubtless free up cash that was previously wasted on delay. Whether this money is reinvested in parts of the justice system that badly need it or end up in Treasury coffers will also be bitterly fought over.

Criticisms that digital court reforms were being applied to justice too fast before the pandemic will still apply even with the new data that would otherwise have taken years to accumulate. In response, the fact that lawyers have managed to rapidly adopt unfamiliar changes will probably be cited for decades to come as proof of their capacity for change.