Study area

Divorce law across the UK

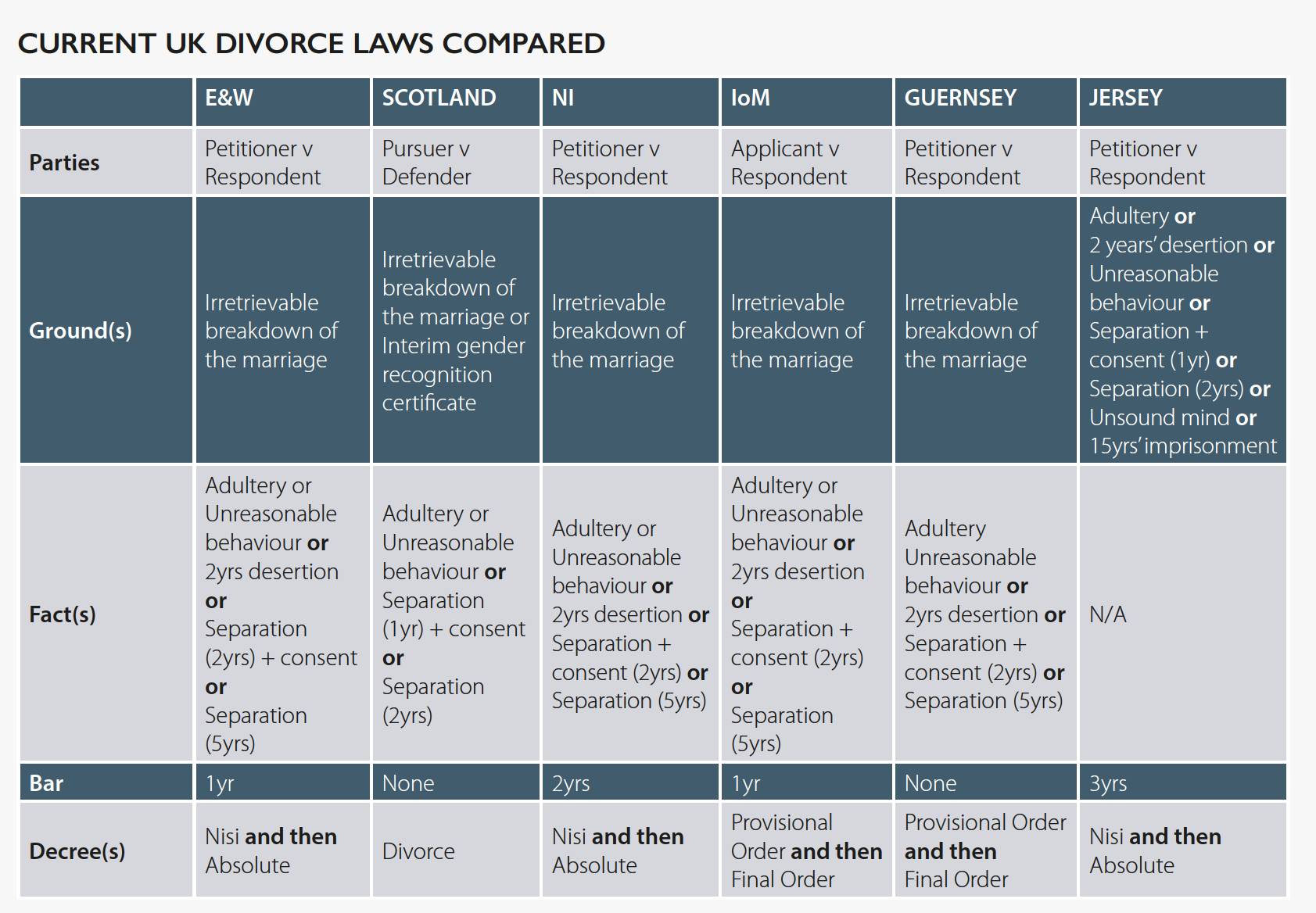

Hannah Roberts compares and contrasts the applicable divorce laws for England and Wales, and for Scotland, Northern Ireland and the UK‘s three Crown Dependencies.

About the author

Hannah Roberts GCILEx is a freelance writer and a former law lecturer.

Looking at the law on divorce is usually one of the more interesting elements covered at the start of studies of family law, and it is probably assumed, by many students, that the position within the legal system in England and Wales is identical to that across the rest of the UK. However, although there is a great deal of overlap, there are also some significant differences. Within this article, the applicable divorce laws for Scotland and Northern Ireland will be considered, alongside those of the three Crown Dependencies of the UK (ie, the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey, including, in particular, the recently proposed changes to divorce law in Jersey) (see Table below).

Since the enactment of the Matrimonial Causes Act (MCA) 1973, there has been just one ground for divorce within the legal system in England and Wales: that the marriage has irretrievably broken down (MCA s1(1)). In order to establish this, the petitioner (that is, the individual who has initiated divorce proceedings) must establish one or more of five ‘facts’, set out within MCA s1(2):

- Adultery by the respondent (ie, the other party to the marriage), which makes it intolerable for the petitioner to continue to live with the respondent;

- Unreasonable behaviour by the respondent, which means that the petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with the respondent;

- Desertion for a period of at least two years of the petitioner by the respondent;

- Living apart for at least two years, with the respondent consenting to the application for divorce; or

- Living apart for at least five years.

In all cases, a petitioner cannot present their request (or petition) for divorce to the court until the marriage has lasted for at least one year (MCA s3(1)). Once the court has approved the application for divorce, a decree nisi will be granted. When at least six weeks have passed from the issuing of this decree, the decree absolute can be applied for, making the divorce final.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, the only difference to the law in England and Wales is that the marriage must have lasted for at least two years before divorce proceedings can commence (Matrimonial Causes (Northern Ireland) Order 1978 SI No 1045).

Scotland

In Scotland, under the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006, there are some key contrasts to note, including that there are two grounds for divorce. The first ground is the same as in the legal system in England and Wales, namely, that the marriage has irretrievably broken down, and, again, facts must be established to support this; however, in this case there are only four. Adultery and unreasonable behaviour remain available, but adultery merely requires that the defender (the Scottish term for a respondent) has committed adultery; there is no additional requirement for the pursuer (the equivalent term for a petitioner) to find it intolerable to continue to live with them.

There are also two separation-based facts, but where there is agreement between the parties to the divorce, only one year’s separation is required. When one party does not consent, then two years’ separation will need to be established. The desertion fact was removed from Scottish law under the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006.

The alternative ground for divorce in Scotland is that one of the spouses has an interim gender recognition certificate (IGRC). This document allows persons who have an ‘acquired gender’, ie, the gender ‘that a person living as a member of the opposite sex wishes to be identified by’ to be legally recognised in that gender (as defined in the Translegal online dictionary). While the existence of an IGRC has no relevance to divorce in England and Wales, it can be used as the basis for an application for having a marriage annulled.

Other differences include that a divorce can be sought within the first year of marriage and that there is only one divorce decree, which is granted once all financial matters have been resolved.

Around the UK, there are a number of islands, including the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islands, ie, the Bailiwick of Jersey and the Bailiwick of Guernsey. The term ‘Bailiwick’ used to describe the separate administrative areas within the Channel Islands, referring to the fact that each area is headed by a bailiff. The islands are not actually part of the UK, but instead form what are known as ‘Crown Dependencies’. This means that, while the Queen is their head of state, they govern themselves having ‘their own directly elected legislative assemblies … legal systems and their own courts of law’, and each island’s legislature makes its own laws.1

The Isle of Man and the Bailiwick of Guernsey2 The law is almost identical to the position within England and Wales and in Northern Ireland, with just one ground for divorce and the choice of five facts through which this ground can be established. The only points of variance are as follows: •

- in the Isle of Man, the parties are referred to as the applicant and the respondent;

- in Guernsey, there is no minimum period of marriage before which a divorce can be sought; and

- in both Dependencies, ‘decree nisi’ and ‘decree absolute’ are replaced with the more modern ‘provisional order’ and ‘final order’.

It is in this jurisdiction that real and substantial differences are found. Although the parties are petitioner and respondent, and the decrees are nisi and absolute, everything else is unfamiliar.

First, the couple must have been married for at least three years before applying for a divorce. Second, the legislation, contained primarily in the Matrimonial Causes (Jersey) Law 1949, identifies seven separate grounds (there are no ‘facts’ ) for divorce as follows:

- The respondent has committed adultery, and the petitioner finds it intolerable to continue to live with the respondent.

- The respondent has deserted the petitioner for a period of at least two years.

- The respondent has behaved in such a way that the petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with the respondent.

- The parties have lived apart for at least one year, and the respondent consents to the divorce.

- The parties have lived apart for at least two years.

- The respondent is of unsound mind and has received at least five years’ continuous care and treatment.

- The respondent is serving a sentence of at least 15 years or life imprisonment.

As can be seen, this divorce law is quite distinct from the other jurisdictions. While there are a number of ‘no-fault ’ options such as the separation grounds (both of which are actually more liberal than that in the legal system in England and Wales) there are also some interesting alternatives, including, in particular, the unsound mind and serious prison sentence grounds. Furthermore, the requirement of a threeyear waiting period is the strictest of all the jurisdictions.

However, the Jersey Law Commission has proposed major changes to the law in order to make divorce on Jersey easier to obtain and less fault-focused.3 Interestingly, if enacted, the proposed laws would move Jersey from being the strictest jurisdiction on divorce within and around the UK to being the most liberal.

In summary, the proposals are as follows:

- There would be no waiting period after marriage before being able to apply for a divorce, making the legal position, in this respect, the same as it is in Scotland and in Guernsey.

- Where the parties to the marriage are in agreement that their marriage has come to an end, they should be able to make a joint statement to indicate their desire to divorce.

- Where one party wishes to divorce, but the other party does not or is not sure, an application for divorce should be able to be made by one party regardless of the length of the marriage, any periods of separation or the behaviour of either party.

So, is the Jersey Law Commission right to consider the move towards a more amicable approach to divorce as the way forward? Is it what divorcing parties want? A simple online search quickly reveals a range of government statistics on divorce. The author examined the available information on divorce in 2010 (which was selected as the most recent date for which the broadest spread of data could be found) from the jurisdictions for which data could be found.4

Looking only at the five main facts/grounds, it is clear that fault-based unreasonable behaviour is the most ‘popular’ fact/ ground to support divorce (used in approximately 45% of nearly 133,000 applications), with the no-fault separation-plus-consent fact/ground coming a long way behind in second place (26%). The separation-without-consent fact/ground and the adultery fact/ground have similar numbers (15% and 14% respectively). However, hardly any petitions were based on desertion (0.37%).

These results vary between jurisdictions, though, for example, adultery-based applications are far less prevalent in Scotland, Northern Ireland or Jersey than in England and Wales. Furthermore, while separation-based petitions accounted for just over 35% of divorces in England and Wales, this type of fact/ground was cited in roughly 72% of divorces in both Northern Ireland and in Jersey, and in nearly 85% of divorces in Scotland.

1Fact sheet on the UK’s relationship with the Crown Dependencies, Ministry of Justice, available at: http://tinyurl.com/h2pt279

2Within the Bailiwick of Guernsey, there are three separate jurisdictions: Guernsey, Alderney and Sark

3Report: Divorce reform, Jersey Law Commission, available at: http://tinyurl.com/j6vfvto

4In 2010, there were nearly 120,000 divorces in England and Wales, see ‘Divorces granted to a sole party: party to whom granted and % fact proven at divorce’, available at: http://tinyurl.com/hyqv7nz. In 2010, there were just over 10,000 divorces in Scotland, see ‘Divorces granted, by ground, 2009-10 ’, available at: http://tinyurl.com/je25v9b. In 2010, there were 2,600 divorces in Northern Ireland, see Statistical Bulletin: marriages, divorces and civil partnerships in Northern Ireland (2010), ‘Table 2(b) Divorces, percentage by grounds, 2000 to 2010’, available at: http://tinyurl.com/k5gmg83. In 2010, there were 246 divorces in Jersey, ‘Appendix C: Divorce statistics for Jersey 2008-2014 ’, see note 3