Family law and practice: too much

While the family court takes a quantum leap in one sphere, there is a warning of an imminent crisis in another. Jocelyn Anderson discusses current case-law and practice issues.

About the author

Jocelyn Anderson is a freelance journalist and a writer.

In 2012, 16-year-old Amina Al-Jeffery, a UK/Saudi-Arabian dual citizen who was born in Swansea and up to that point had lived all her life in Wales, travelled unwillingly to Saudi Arabia at the insistence of her father, Mohammed Al-Jeffery. She has been there ever since in increasingly controversial circumstances, which include press allegations that Amina Al-Jeffery is (or was) being kept in a cage.1

Amina Al-Jeffery’s application to the family court for an order that her father should permit her to return to the UK has crystallised and redefined the protection that the UK courts can afford vulnerable British citizens abroad, particularly women and girls who are either under family constraints or undue influence from relatives and in another jurisdiction (Al-Jeffery v Al-Jeffery (vulnerable adult; British citizen) [2016] EWHC 2151 (Fam)). The judgment made clear that the ‘constraints’ involved in Amina Al-Jeffery’s case would be taken very seriously indeed by the British courts, and that, even if they are habitually resident in another country, applicants can ask the UK courts to intervene where the circumstances are appropriate (para 54).

The full details of Amina Al-Jeffery’s past and current circumstances are detailed in the two published judgments ([ 2016] EWHC 2151 (Fam) and [2016] EWHC 2309 (Fam)); however, it is important to note the following:

Amina Al-Jeffery did not go willingly to Saudi Arabia.

She has consistently expressed a very clear wish to return to the UK.

She made very serious allegations about physical abuse as well as restrictions of her physical liberty during the past four years.

Mohammed Al-Jeffery accepted that he has, for at least some period of his daughter’s residence in Saudi Arabia, locked her into her bedroom by means of a metal barrier put up inside his Jeddah flat, and that he has refused to allow her access to a telephone or computer.

...the clarity of decisionmaking and the gravity of the problem presented [in Al-Jeffery ] makes this an important ruling, with which advisers should be familiar

Mohammed Al-Jeffery’s view, strongly expressed, is that he was taking these steps for his daughter’s own good because of what he considered to be her inappropriate behaviour, including running away from home in Jeddah on two occasions. He has refused to comply with orders that he should allow Amina (who is now 21) either to attend a UK Consulate or Embassy to speak to her solicitor, or indeed to speak to her solicitor directly or unsupervised anywhere else. While there is clearly a clash of cultures here, Holman J noted that, under the law and culture of Britain, the extent of the constraint was ‘totally unacceptable’ (para 54).

Saudi Arabia does not recognise dual nationality, and therefore does not recognise Amina Al-Jeffery’s British citizenship. Although the question of her habitual residence has not been definitively decided, it was agreed that she was no longer habitually resident in England and Wales.

The extent of Amina Al-Jeffery’s physical imprisonment is extreme, but there are certainly women and girls of UK nationality facing the same kind of problems elsewhere in the world. What, if anything, can UK courts do to help? Have they any … jurisdiction to interfere? If they have, when and how should this be exercised?

The existence of the High Court’s jurisdiction in relation to vulnerable adults is now well-established ; it is, in essence, the same as the inherent jurisdiction in relation to children. ‘Vulnerable adults’ are not just those with mental incapacity: the category includes those who are reasonably believed to be under ‘constraint or … subject to coercion or undue influence’ (In the matter of SA A local authority v (1) MA (2) NA (3) SA (by her children's guardian LJ) [2005] EWHC 2942 para 77, per Munby J). In this case, the jurisdiction applied to the applicant on the basis of her British nationality, and the fact that she was no longer habitually resident in the UK was not an impediment, although it was obviously a factor. However, in cases where nationality was the sole ground for the jurisdiction, the court had to exercise great caution. (See In the matter of A (Children) [2013] UKSC 60, concerning jurisdiction and the return of a child. Lady Hale, giving the lead judgment, said that ‘extreme circumspection’ was called for in deciding to exercise the jurisdiction (para 65)).

There are obviously difficulties in attempting to enforce a UK order in a country with no reciprocal enforcement arrangements, or where the proposed order does not fit into an existing reciprocal arrangement or might result in two conflicting decisions: one in each country.

Saudi Arabia has no reciprocal arrangement or convention with the UK, so in Amina Al-Jeffery’s case enforceability was clearly an issue. Furthermore, there had, in fact, been a kind of consent order made in Saudi Arabia in April 2016 under which Amina Al-Jeffery had apparently undertaken not to challenge her father’s authority ‘over all her affairs and not to leave the house without his permission’ ([ 2016] EWHC 2151 (Fam) para 28). Indeed, the very wording of this order caused Holman J serious concern on the point of constraint or control, particularly the fact that it appeared to cover all of Amina Al-Jeffery’s decisions.

In spite of this order, the applicant was still, as far as the court was aware, expressing a wish to leave Saudi Arabia and return to the UK, and had not withdrawn her application. The restrictions preventing Amina Al-Jeffery from communicating freely with her solicitor throughout have been both a significant impediment and a major concern for the court.

Holman J considered that even though there was no prospect of direct enforcement of his order in Saudi Arabia, and even though it would conflict with the April 2016 order made in that country, he would order that Mohammed Al-Jeffery facilitate his daughter’s return to the UK. The judge noted that it was unlikely that Amina Al-Jeffery would have free access to the Saudi Arabian courts; that she certainly would not have the funds for a lawyer; and that he did not have confidence that the Saudi-Arabian courts would make an order that she should be returned to the UK, in large part because they would not recognise her British nationality.

On the enforcement point, although Mohammed Al-Jeffery had no assets in the UK, his wife and several of his children lived in the UK; if the respondent were in breach of an order, he would clearly find his ability to visit them restricted, which gave the court a ‘considerable moral and … practical ‘hold’ over him’ ([ 2016] EWHC 2151 (Fam) para 60). So, an order was made that if the applicant chose to return to the UK, the respondent should facilitate that arrival by 11 September 2016. Holman J also provided that if the applicant did return to the UK, she should attend the restored hearing.

There are two other important factual elements which persuaded the judge to exercise his discretion. Amina Al-Jeffery had not chosen to travel to Saudi Arabia in 2012, and had, from the beginning, made it clear that she wanted to come back to the UK. She had also been brought up and educated in the UK until she was nearly 17: culturally, therefore, her life had a very specific British dimension. The judge said that he would have taken a very different view of the case if the applicant had lived her whole life in Saudi Arabia and had been British only by descent.

While it is unlikely that in everyday practice family law practitioners will need to refer to Al-Jeffery, the clarity of decision-making and the gravity of the problem presented makes this an important ruling, with which advisers should be familiar. When clients in Amina Al-Jeffery’s position need advice, it must be clear and quick.

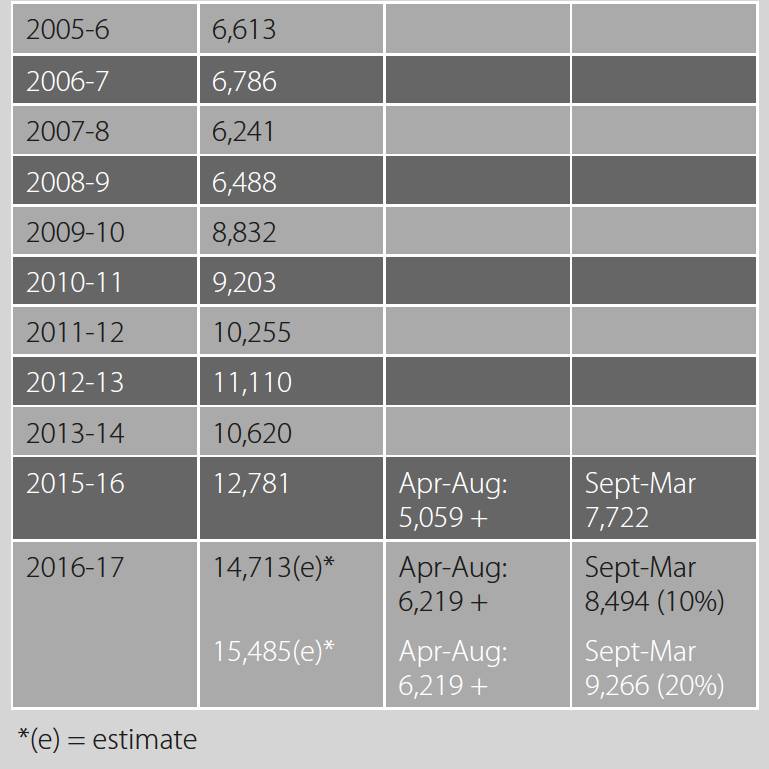

While the court extends its jurisdiction to citizens abroad, however, Sir James Munby president of the Family Division has warned of imminent trouble for the vulnerable here at home.2 In his latest View from the President’s Chambers, Sir James points out that, in very rough numbers, the family court’s care caseload has more than doubled annually, and resources are stretched to the limit (see Table). He comments that there is no slack left in the system and, most alarmingly of all, ‘no clear strategy’ to manage the crisis. The family court’s resources (whether of judges or otherwise) are not being increased, while the number of care cases could, if the brakes are not applied, hit over 25,000 per year by 2019–20. The result is, as he notes, an impending crisis within the court system and a very significant impact on the total legal aid budget.

Further research, says Sir James, is ‘desperately needed’, and although he did not make clear which agency should carry out the study, this edition of the View from the President’s Chambers seems to be addressed as much to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and to HM Courts and Tribunals Service as to the profession. There is no hope of applying the brakes effectively unless we can understand why the number of care cases is growing at such a rate and do something about it. Nor can the flow of cases through the system be better managed without analysis of what is happening in the courts.

Although the president’s views have been endorsed by court staff and social workers, to date there has been no response from the MoJ. The cynical view would be that research on this scale costs serious money, and in the current political climate the MoJ will not fund it despite the fact that this may, of course, increase costs further down the line. However, if the reform of legal aid has taught us anything, it is that in this regard the MoJ has form, so watch this space!

1 See James Cox, ‘Daughter held prisoner: British Muslim, 21, kept in a cage in Saudi Arabia by her dad since she was 16 because he disapproved of her Western lifestyle’, Sun, 27 July 2016, available at: http://tinyurl.com/ja88xyt; and Will Worley, ‘British woman 'kept in cage in Saudi Arabia by father who disapproved of her behaviour’, Independent, 27 July 2016, available at: http://tinyurl.com/gw8kmhw

2 View from the President’s Chambers: Sir James Munby, President of the Family Division. Care cases – the looming crisis, (15): September 2016, available at: http://tinyurl.com/hhvbv5r