Administration of justice update

Administration of justice update: probate fees increase: will they or won’t they?

Emily Deane discusses the new probate fee regime which is due to be implemented by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) in May 2017.

About the author

Emily Deane TEP is Technical Counsel at STEP.

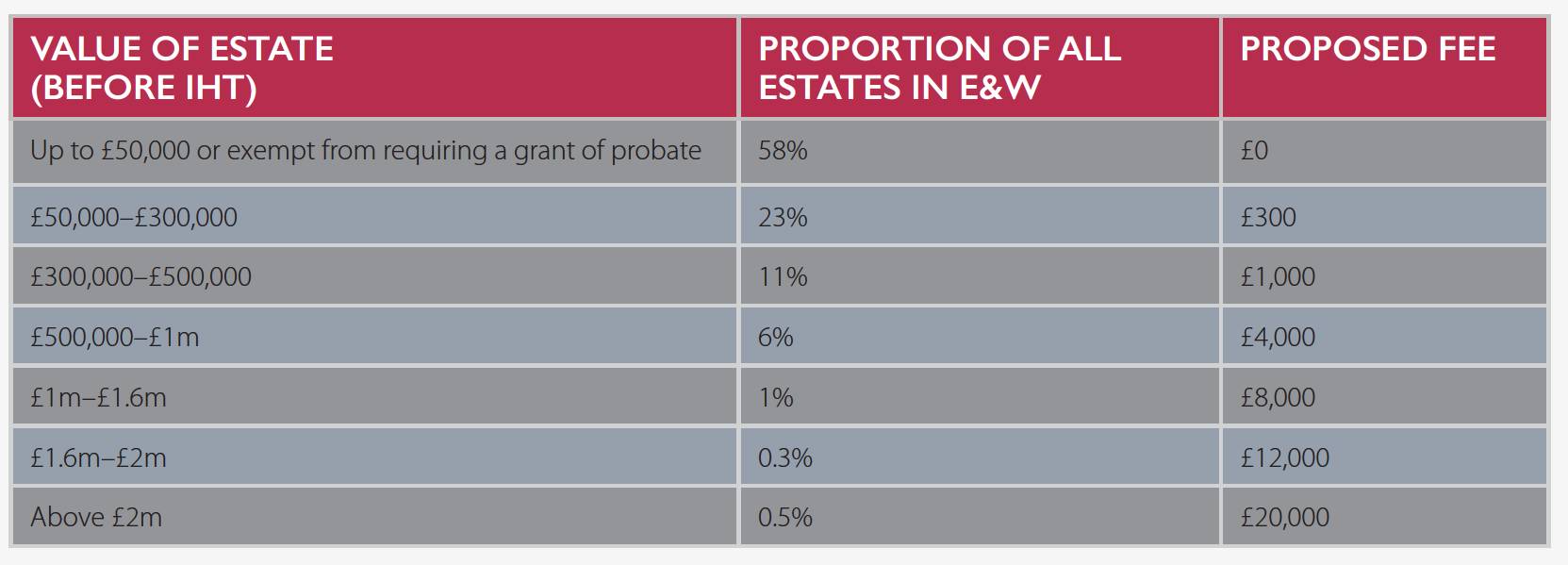

D espite the 97.5% opposition to the consultation on fee proposals for grants of probate last year, the MoJ announced that it is implementing the new fee structure, starting May 2017. The announcement was made in March, giving a surprisingly small window of less than two months to implement the new regime. The significant uplift in probate application fees has been branded as a stealth death tax due to the fact that is based on an ad valorum sliding scale and, in some cases, the fee may increase up to 9,000%. This measure could see families having to take out significant loans just to complete the legal formalities after the death of a relative, adding to the stress of bereavement.

Since the announcement that the fees are being replaced by the new system, there has been a lot of speculation surrounding the controversial decision. The Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments met in the House of Commons, on 29 March, and assessed that the MoJ needs express permission in order to impose what constitutes a new tax, and that the Lord Chancellor, Elizabeth Truss, does not have authority to do so. The committee agreed that there should be ‘no taxation without the consent of parliament, which must be embodied in statute and expressed in clear terms’ (para 1.12). The committee concluded that it is not sufficient to pass the new probate legislation by way of a Statutory Instrument.

It has been widely acknowledged that the new application fees will be completely disproportionate to the level of service provided by the probate court and will incur further stress for grieving families. In addition, it seems grossly unfair that the extra £300m per annum which will be generated in income will be used to fund the other courts and the Tribunal Service and not the probate court. The new fees are still due to be implemented in May; however, it is unclear whether the government will be able to enforce the new provisions or determine them to be unlawful.

The new fee system will be based on a sliding scale of value, and will apply to all estates worth £50,000 and over. An estate of £300,000–500,000 will have to pay a £1,000 fee and estates of £2m or more will pay as much as £20,000. A family with an estate worth just over £1m, which is not at all unusual given the current housing market, will not only have to pay a sizeable inheritance tax (IHT) bill, but also an additional probate ‘fee’ of £8,000 as opposed to the current fee of £155. It would be extremely difficult not to concede that this is the introduction of an additional death tax rather than an administration fee.

It is unclear how some executors will be able fund payment of the fees if there are inadequate estate funds available. The executors may have to apply for a loan to finance the application fee using the estate as security. This will more than likely incur delay, cost and administrative burden to the detriment of the executors and the beneficiaries. Form IHT423 was introduced, in 2008, to assist with the payment of IHT due from an estate. Yet experience shows that some banks will not accept this application, and will not comply with this request from a practitioner or an executor. Banks are also likely to be reluctant to provide this kind of financing for the probate fee, particularly at its highest level. Further to the enhancement of money laundering regulations, it will probably be increasingly diÿcult to obtain loans for this purpose.

In addition, is it legally sound for an executor to charge the assets of an estate as security for a loan? If the executor does not obtain a grant of probate or it is delayed, does the financial institution have the right to recover the advanced funds from the assets purportedly charged to it? While most financial institutions are willing to enable a grant to be obtained, they are coming under increasing pressure to ensure that any lending is protected appropriately.

In the event that there are ample estate funds to cover the fees, they cannot usually be accessed before the grant of probate unless the banks provide funding. Some of the banks will already be providing loans for the payment of IHT, therefore it seems unlikely that they will find it acceptable to lend even more. We also understand that bank policy is, in general, not to release funds for court fees, which is how the probate fee would be classified. The government proposes, in its response paper, that executors should be able to take out a loan to pay the fee, which is an unrealistic proposition should an executor have a poor credit rating and when short-term loans can be shackled to interest rates that are extortionately high.

We note that there will not be an instalment option available to pay the fees, like IHT, and executors will be able to apply to the Probate Service to sell an asset. What will happen in the circumstances where the only asset is the property and it is unable to sell? There are many uncertain scenarios.

There are concerns about the cut-off date between the old and new system. The Probate Registry has confirmed that the implementation date will be in May and the new fees will apply to all applications received by the Probate Service on or after the implementation date – irrespective of the date of death.

The government clearly anticipates that there will be a rush to ensure that applications are submitted by the cut-off date; therefore, it seems prudent to lengthen the transitional phase to avoid cost, delays and grievances. It would be far more equitable to extend the cut-off date for application submissions, since two months’ notice is not sufficient to get a reasonably sized estate in order. It would be grossly unfair to increase the fee by such a significant amount during the administration when the clients have already budgeted for the lower probate fee. Alternatively, the cut-off date could be substituted for a date-of-death period, for example, anyone who dies before 1 August 2017 will be charged under the old system.

The level of potential liability for a practitioner, who is subject to unavoidable delays in the submission of an application and is subsequently lumbered with the new fee, is unclear. If the client has been informed by their practitioner that the estate will be paying the lower fee, will the client have a right to claim damages? Should firms be sending out an addendum to their terms of engagement letter, instructing clients that they may be subject to the higher fee? In any event, the client may feel that the practitioner should have submitted the application more expeditiously to avoid the extra cost.

The government asserts that the benefit of the additional residential nil-rate band, in 2017, will outweigh the increased probate fee; however, there is no corresponding benefit or interplay with IHT rates and the probate fee is simply a significant and additional cost. The requirements are overly complicated, and for estates over £2m the tax benefit is reduced incrementally until it is completely unavailable for estates over £2.35m. The tax relief will only be applicable in certain circumstances, and will provide no ‘offset’ where the estate is left to a surviving spouse, civil partner or charity. The MoJ also defends the new regime by claiming that it will exempt more than 50% of estates from payment of a fee, and over 90% will pay less than £1,000 in fees. However, the vast uplift to the fees of the remaining estates is unpalatable and, potentially, unconstitutional.