Insurance

The Insurance Act 2015: a new regime in insurance law?

Gerald Swaby considers whether the ‘biggest reform to insurance contract law in more than a century’ has heralded a new regime in insurance law.

About the author

Gerald Swaby is a senior law lecturer at the University of Huddersfield.

The Insurance Act (IA) 2015 consists of seven parts, but for the purpose of this article’s overview the first five parts shall be considered briefly:

- Part 1 deals with definitions of an insurance contract;

- Part 2 introduces a duty to make a fair presentation of the risk;

- Part 3 deals with warranties and terms;

- Part 4 considers fraudulent claims and Part 4A addresses the insurer's duty to pay a claim within a reasonable amount of time; and

- Part 5 deals with contracting out of the first four parts.

In some cases, it can be said that the IA represents a radical change in insurance law that has not been seen since the Marine Insurance Act 1906 (MIA) was passed and, given that the MIA codified much of the common law from the mid-1760 s onwards, this is indeed a welcome change. While change can be a good thing, this particular Act’s provisions could be undermined by expressly contracting out. Then the previous common law position can actually be restored, thus undermining any change when dealing with non-consumers.

IA Part 2 ss2 to 8 considers the duty on the insured to make a fair presentation of the risk. The common law concepts of avoidance for a breach of upmost good faith, under MIA s17, is for the main part repealed insofar as a breach of section 17 allowed for the contract to be avoided from its inception.

However, in the case of non-consumers it could be said, in relation to disclosure, that the IA operates in a similar manner to non-disclosures and misrepresentations under MIA ss18–2020. While the wording in relation to disclosures under the MIA is different, it has effectively been revised and has reintroduced, through the IA, a similar approach using equivalent wording.

The duty of disclosure is part of the duty to make a fair presentation of the risk under section 3. The presentation of this risk has to be fair. This means that the disclosure must be one that is made reasonably clearly and is accessible to the prudent insurer.

Enterprise Act 2016 ss28 and 29 introduced Part 4A into the IA to allow the insured to be compensated where the insurer has not paid a claim promptly. The… provisions…come into force from 4 May 2017 and amend various sections of the IA

The prudent insurer is an objective test, and this mirrors the provisions under the common law before the IA. This requires that every material representation of a fact has to be substantially correct (under s3(3)( c)), and if it relies on the insured’s expectation or belief it is sufficient that it must be made in good faith.

What must be disclosed under section 3(4) is every material circumstance that the insured knows or ought to know. If the insured fails to make such a disclosure of material fact, then it will be sufficient that the insured provides information which places a prudent insurer on notice to make further enquiries. This is an objective test in the insurer’s favour, and if the insurer fails to enquire about a circumstance then the insured does not have to make a disclosure if:

- [it] diminishes the risk;

- the insurer knows it;

- the insurer ought to know it;

- the insurer is presumed to know it; or

- it is something about which the insurer waives information.

As a matter of common practice, it will now require the insurer to adopt a more proactive stance (ie, asking more questions of the insured), and if the insurer fails to do this they will no longer be allowed to rely on the remedy of avoidance, unless the statement was deliberate or reckless under IA Sch 1 s2 or if the insurer can show that they would never have entered the contract under any terms.

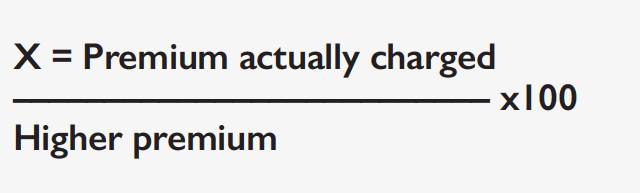

However, where there has been a breach of non-disclosure by the insured, the remedy is now proportional under IA Sch 1 s5 where the insurer would have entered the contract, but on different terms (excluding those relating to the premium.) So, if the insurer would have contracted on different terms, the proportional remedy is based on the statutory formula:

If the insurer would have acted differently and entered the contract with an exclusion clause for a particular term and if the risk fell into that exclusion clause, the insured will not be entitled to a proportionate remedy. This could be a trigger for the proportionate remedy, if the insurer would have entered the contract on different terms. In this case, different terms could be a term concerning the insured’s excess where the insured’s contribution would be higher: this would trigger the proportionate remedy. However, if, for example, the insurer would have excluded the risk of subsidence had they known the full facts then, provided that the subsidence damage to the insured’s property fell within this definition, the insured could not recover any indemnity.

Under IA Part 3, section 9 is particularly important as it abolishes the use of a term to make pre-contractual representations the basis of the contract and section 10(1) abolishes avoidance if the insured is in breach of a warranty.

Section 10 also provides that warranties should be treated as suspensory conditions/terms, that is to say the risk is not covered if there is a breach, but if the insured starts to comply with the term the cover is restored.

IA Part 4 ss12 and 13 deals with fraudulent claims. Much has been written on this area by academics and practitioners, and it is highly likely that this will continue. With this in mind, the Law Commission wanted to provide some certainty for insurers regarding their remedy when there has been a fraudulent claim, and this is covered under section 12.

Under section 12(1), the remedies are clear:

- the insurer does not have to pay the fraudulent claim;

- the insurer can recover any payments made in relation to that claim; and

- in addition, the insurer can terminate the contract from the time of the breach.

Where the insurer does terminate the contract, all future liability ceases and, under section 12(2), they can keep any premiums paid.

However, if there has been a genuine claim before a fraudulent claim, then the genuine claim stands and cannot be disturbed as avoidance is no longer possible under the reforms.

Questions have been raised about whether the fraudulent claims rule extended to fraudulent ‘devices or means’ or ‘collateral lies’ as they have now been termed by the Supreme Court in Versloot Dredging BV and another v HDI Gerling Industrie Versicherung AG and others [2016] UKSC 45, paras 38 and 39 respectively. This is a situation where there has been a genuine loss, but the insured has told a lie that is irrelevant to the loss. In Versloot, the manager of a cargo ship, the DC Merwestone, told a lie to the insurer, to the extent that an alarm had sounded on the bridge of the ship when this was not the case. The amount at stake was over €3.2m. The lie was not dishonest, as the ship’s manager genuinely believed it to be true, but nevertheless the statement was reckless. The lie was disproportionate to the loss of the insured. This decision was painted by the insurance sector as being a bad day for honest policyholders, and that as a result premiums could rise.

However, in case anyone becomes excited by the idea of committing fraud against an insurer, there are some major considerations to be taken into account. First, those who admit to committing fraud will effectively be blacklisted in the anti-fraud databases, and so they will find it difficult, if not impossible, to get any insurance cover ever again. Second, there is the criminal sanction under the Fraud Act 2006.

The approach to collateral lies is nothing new to the industry: the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) has been treating such lies as immaterial for some years.1

Part 5 concerns the insurer’s right to contract out of the provisions of the IA under sections 15–18. From a consumer perspective, it is possible to contract out of IA Parts 3 and 4. However, the IA acts as minimal provisions, thus any terms that put the consumer in a worse position than under the IA have no effect.

For non-consumers, it is a different issue. It is possible for an insurer to contract out of the provisions in Parts 2, 3, 4 and 4A, but in order for the terms to be binding on the insured, they have to satisfy the requirements in IA s17 otherwise the disadvantageous terms have no effect.

Section 17 of the IA requires that the disadvantageous term should be brought to the attention of the insured before the contract is entered or a variation agreed. The term must be clear and unambiguous. This is nothing more than ensuring that the principles of the common law of contracts are included.

The IA came into force on 12 August 2016, but that date did not apply to the late payment of insurance claims. Even before the ink was dry on the IA, it was amended. Enterprise Act (EA) 2016 ss28 and 29 introduced Part 4A into the IA to allow the insured to be compensated where the insurer has not paid a claim promptly. This provision was included in the original IA, but as it was a Law Commission bill, it went through the non-contentious procedure. Unfortunately, some in the insurance market objected to this provision, and it was removed from the original IA.

The EA provisions relevant to insurers come into force from 4 May 2017, and amend various sections of the IA.

IA Part 4A introduces a statutory implied term that an insurance claim should be paid within a reasonable period of time, which allows for the investigation and assessment of the claim. As ever, what is ‘reasonable’ will be up to the judiciary, but there is a need to take into account the types of insurance and the size and complexity of the claim. Other factors that will be pertinent could relate to any relevant statutory provisions or regulatory rules that insurers are compelled to follow under Part 4A s13A.

The insurer has the right to use an express term to contract out, but not in the case of consumers: IA s16 has to be followed. Any claim against an insurer must be made within one year under Limitation Act 1980 s5A.

Even though these amendments have been made to the IA, an insured will have an uphill struggle: first, the insured must prove that they have a valid claim and, second, they will have to prove that the insurer did not pay the claim within a reasonable time. This is going to be very fact dependent, and will have to take into account the type of insurance involved and allow the insurer a reasonable period to conduct an investigation to establish their liability and whether they have reasonable grounds for not paying the damages (for example, an excluded risk or fraud). Third, the insured will have to show that they suffered loss resulting from the failure to pay, and that this loss was foreseeable at the time of contracting. This will have to take into account both limbs of Hadley v Baxendale [1854] EWHC J70. Finally, the insured must mitigate their loss.

The need for this provision comes out of the arguably unjust state of the English law in Sprung v Royal Insurance (UK) Ltd [1999] 1 Lloyd's Rep IR 111. Sprung insured his factory, and then vandals gained entry causing £75,000 worth of damage to machinery. The insurer attempted to under settle the claim. Sprung refused: he wanted his full indemnity. Sprung’s stance was due partly to the action of a previous insurer’s sharp practice to underpay claims, which had left Sprung substantially out of pocket).

As Sprung could not afford to replace the damaged machinery, his business failed six months later. The insurers made a deliberately late payment four years later. Sprung asked the Court of Appeal to award damages for the deliberate late payment of indemnity. The Court of Appeal held that it was bound by the ‘hold harmless’ principle. This is a legal fiction that imposes liability on the insurer to stop the risk from occurring (Firma C-Trade SA v Newcastle Protection and Indemnity Association (the ‘Fanti’ ; Socony Mobil Oil Co Inc and others v West of England Ship Owners Mutual Insurance Association (London) Ltd (the ‘Padre Island’') [1991] 2 AC 1, per Lord Goff at para 35).

Thus, if the facts of Sprung were to occur under these sections, it can be seen that Sprung would have had a valid claim. The insurer had clearly dragged their heels in making the payment, which would have resulted in loss. This loss to Sprung’s business would be as a direct result from not being in a financial position to replace the damaged machinery, and it would have been foreseeable, at the time of contracting, that such a late payment would contribute directly to his business loss.

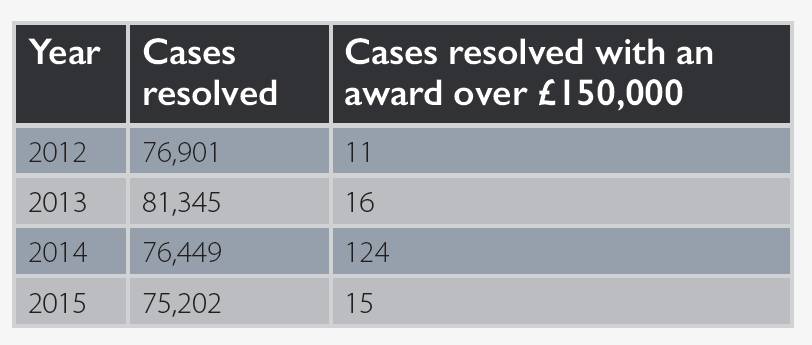

Assuming that brokers and agents continue to hold insurers to their duties under the IA, the Act will clearly be beneficial to the insured. However, it will not be long - given the litigious nature of insurance – before any related disputes reach the courts, and there may even be a few complex consumer or small business cases that fall outside FOS’s free complaints service criteria (see table above, which sets out the amount of claims FOS handled in the relevant year and how many were resolved with an award over £150k. The information, which was a Freedom of Information request to FOS, gives the latest figures available at the date of the request).2

- ‘Aspects of insurance fraud', Ombudsman News, issue 41, November 2004, available at: www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk/publications/ombudsman-news/41/41.pdf

- FOS has a compensation limit of a maximum of £150,000. Since 2012, there has been an average of 77,474 cases per year. However, those cases that exceed the £150,000 limit are in general small, ie, an average of 0.2%. While it could be said that the limit prevents the development of common law by removing those cases which could go to court and, potentially, advance case law, FOS can still make a direction order for those claims up to £150,000 and make recommendations for sums over that amount. However, the insurer does not have to follow the recommendation, and whilst this is not expressly stated on the FOS website, FOS will tell the insurer that they should pay the claim in accordance with the terms of the policy, and if the insurer refuses the insured should be able to compel the insurer to meet the claim in court. Visit: http://tinyurl.com/os39v6n