Cover story

Housing matters: fairness matters

The work of the Housing Ombudsman Service

Denise Fowler reflects on the achievements of the independent housing complaints resolution service, and reveals its future plans.

About the author

Denise Fowler is the Housing Ombudsman for England.

I have been the Housing Ombudsman for England for just over two years. I am moving on, in June, to a more front-line role as chief executive of Women’s Pioneer Housing, so this is an opportunity to reflect on all that has been achieved and what more the Housing Ombudsman Service (HOS) has planned for the future.

I was appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government under Housing Act (HA) 1996 s51. My role is to enable tenants, and other individuals, to have complaints about member landlords investigated in accordance with a scheme approved by the secretary of state and to administer the scheme.

The current Housing Ombudsman Scheme was approved by the secretary of state on 1 April 2013. Under the terms of the scheme, my role is as follows:

- to resolve disputes involving members of the scheme; and

- to support effective landlord-resident dispute resolution by others.

When I started in March 2015, my priority was to ensure that in fulfilling this role we provided the best possible service for our customers. I consulted with staff, our member landlords, and tenant and resident organisations to develop a new vision and strategy, and over the past two years we have set about making this a reality.

The new vision ‘Housing matters: fairness matters’ recognises the importance of housing to people’s lives and the uniqueness of housing complaints. Landlords and residents have an ongoing relationship, so if things go wrong, issues can escalate and relationships sour. Residents need to have confidence that any issues they raise will be dealt with fairly and impartially, whether by their landlords or by us at the HOS.

In 2015–2016, we had 2,368 landlord members, representing 4,751,430 housing units as at 31 March 2016. By the end of December 2016, this had risen to 2,477 members, representing 4,773,274 households. The HA 1996 ensures that our remit covers all registered providers of ‘social housing’ (as defined in the 1996 Act) in relation to all their housing activities (Sch 2, para 1) and all local housing authorities in respect of their ‘housing management functions’ (Sch 2, para 1A). A number of private landlords join as voluntary members (as permitted by Sch 2 para 3).

- Residents (ie, tenants, licensees, shared owners, leaseholders) of housing associations and local housing authorities.

- Residents of private landlords may also be able to complain if the landlord is a voluntary member of the scheme.

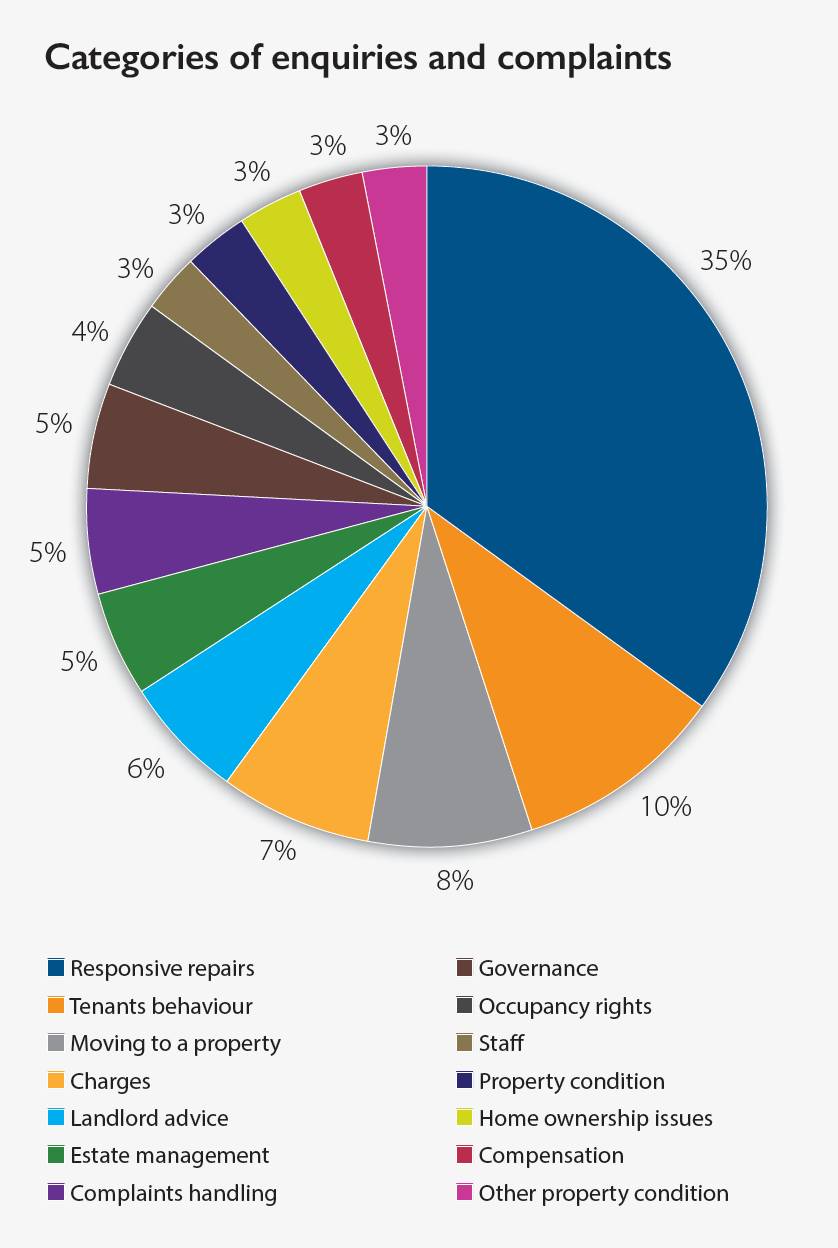

The breakdown of complaints received from April to December 2016 is set out in the chart below. Our complaint categories have remained fairly consistent over recent years, with the largest category being responsive repairs.

It is an easy and a common assumption that ombudsmen are solely a final-tier redress route, and that a dissatisfied customer can only go to an ombudsman when every other avenue has been exhausted and they are still without a satisfactory solution or redress. While this is true of most other ombudsmen, the Housing Ombudsman is different.

Our dual role means that we are heavily involved in local resolution, both before and during the landlord’s own complaints procedure; in fact, 83% of enquiries and complaints that came to us between April and December 2016 were resolved without the need for a formal investigation, ie, they are resolved at either local resolution or early resolution stage. Ultimately, the number of complaints that we can help to resolve early is one of the key criteria against which we judge the effectiveness of the organisation because we know that early is best, both for residents and for their landlords.

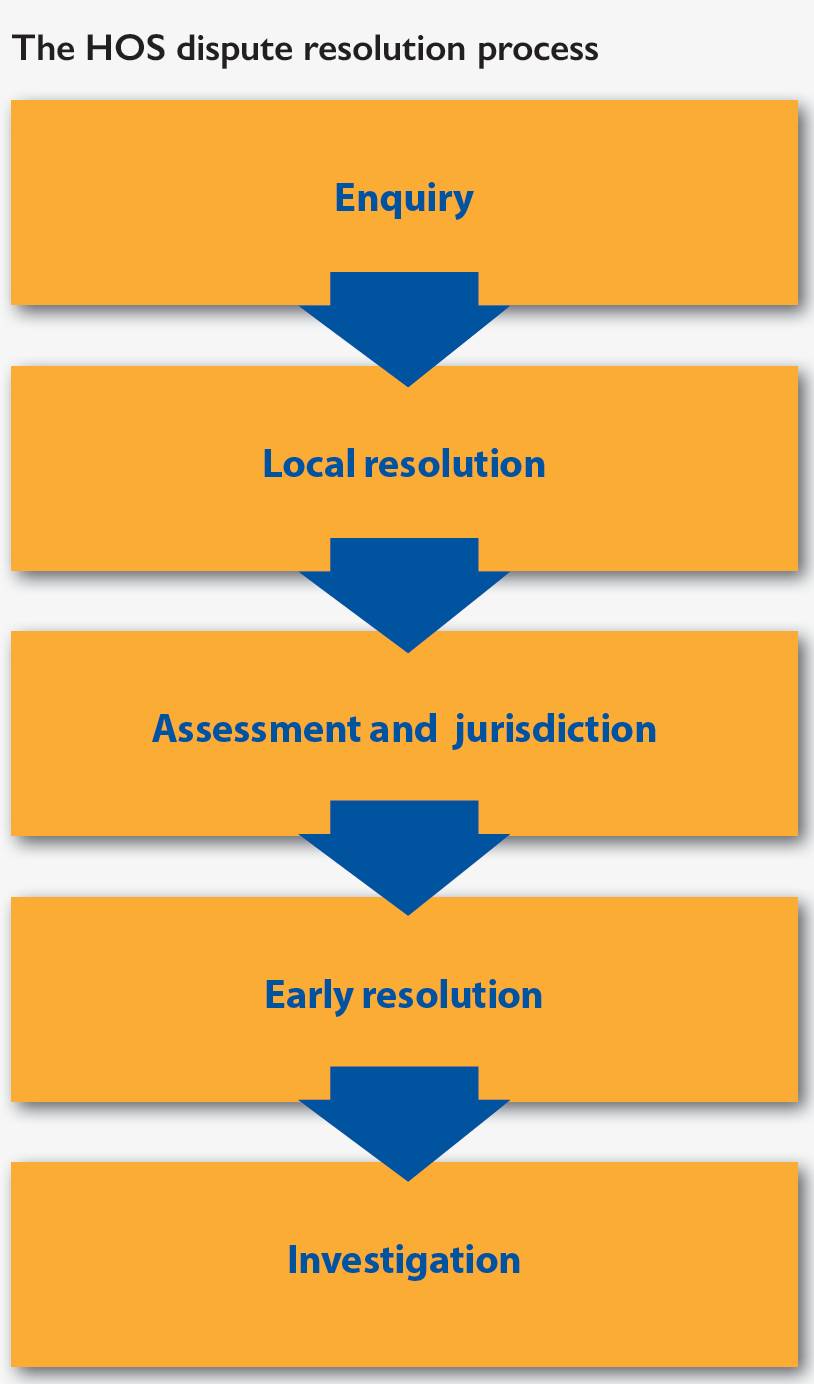

In April 2016, I introduced a new resolution process at the Housing Ombudsman Scheme (see). This has provided greater efficiency, and also greater clarity and transparency to complainants. The process aims to resolve cases as early as possible, but also sets out what happens as a case progresses through the stages of our process.

At local resolution stage, the Housing Ombudsman has a power to promote the local resolution of disputes, including on premature complaints (see HA 1996 Sch 2, para 10 and Housing Ombudsman Scheme paras 33 and 34). Once a complaint has been through our assessment and jurisdiction process, ie, we have ensured that the complaint comes within jurisdiction and is one which the ombudsman is entitled to investigate, we will work with the landlord and the resident to attempt to resolve the dispute fairly and to the satisfaction of all parties: this is our early resolution stage of the process.

Our independent status, combined with our experience and expertise in investigating and resolving complaints, means that we are well placed to encourage complainants and landlords to take a fresh look at the issue and explore possible options that can lead to a satisfactory and amicable outcome. If we can resolve a case through this process, then we will. Once agreement is reached, the ombudsman will issue a determination reflecting the terms of that agreement.

Early might be best, but there will always be some cases where a dispute cannot, for whatever reason, (for example, complexity or breakdown of the landlord/tenant relationship) be resolved without detailed and considered examination of the evidence. So, too, there will always be cases where complainants do not seek help from the ombudsman until after their landlord’s complaint procedure has been exhausted. In such cases, we will carry out an investigation, providing the final tier of redress for the complainant, and put things right. My authority to investigate is set out in HA 1996 Sch 2 s51 and paragraph 25 of the approved scheme.

The Localism Act 2011 amended the HA 1996 to provide that residents who remain dissatisfied with their landlord, once their complaint procedure is finished, can ask for their complaints to be considered by a ‘designated person'. A ‘designated person’ can be an MP, a local councillor or a designated tenant panel, and they can bring the complaint to the ombudsman on the complainant’s behalf.

Complainants who do not choose to bring their complaint through a designated person must wait eight weeks after the landlord’s complaint procedure has been completed before they can bring their complaint to the ombudsman for investigation.

A complaint is ‘duly made’ to the ombudsman when:

- the complainant has completed the landlord’s complaint procedure and either:

- eight weeks have passed since that date; or

- the complaint has been referred by a ‘designated person'; and - a signed complaint form, giving the Housing Ombudsman permission to share information about the case with the landlord, has been received.

The second limb of our role is what makes us different from a lot of the other ombudsmen. It is also another reason the Housing Ombudsman is so different from a court. Our approach is inquisitorial rather than adversarial: housing complainants who want an alternative to the expense, formality or combative approach of a court can bring their disputes with their landlord to the ombudsman at any stage.

Where a complainant contacts us before the landlord’s complaint procedure has been completed, the Housing Ombudsman’s expert staff will provide guidance to help them navigate their landlord’s complaints procedure as well as helping them to articulate their complaint clearly.

A clear complaint, ie, one that identifies the precise source of the problem and the action needed to put things right is crucial: it gives the complainant the best chance of getting a solution to their problem because it helps the landlord understand what needs to be done to make things right. It can be easy for problems to escalate and the actual reason for the dispute to get lost as relationships between the resident and the landlord sour. Landlords have rarely been under as much financial pressure as they are currently, and are trying to do a lot with very limited resources; however, this does not make a resident’s problem any less pressing or real, and it is in everyone’s interest for that relationship to remain amicable.

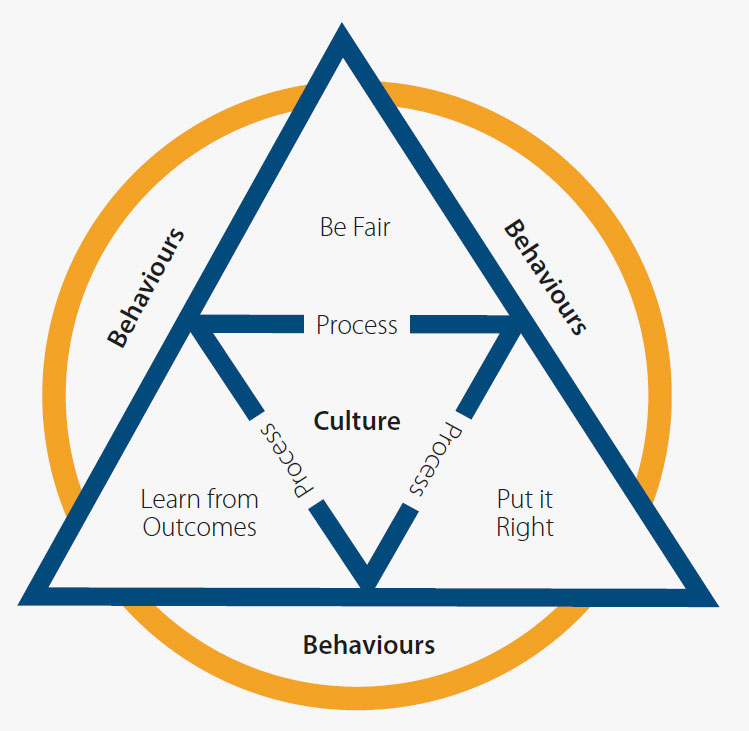

That is where we at the HOS can have a critical role. From the enquiries and support stage through to our detailed consideration of disputes, we will use our dispute resolution principles illustrated below: be fair (ie, treat people fairly and follow fair processes); put things right; and learn from outcomes.

As well as applying the dispute resolution principles ourselves, we encourage our members, residents and designated persons to use them too. Landlords can use them as a good practice guide in complaint handling to improve success in resolving disputes, encourage better relationships and save resources. Residents should be able to expect that their landlord will use the principles in handling their complaint, but they can also use the principles as a guide to make their complaints more effectively.

An organisation’s culture must be right for the complaint-handling process to resolve disputes effectively and in order to learn from outcomes. While a good procedure and well-trained staff will achieve results, for maximum impact a positive complaints culture is essential. Although the three principles are simple, applying them effectively means having the right culture, process and behaviours; the relationship between the principles and culture, process and behaviours is demonstrated in the triangle diagram.

Over the past two years, we have resolved more cases than ever before. Included within these cases is a very significant increase in the number determined within our formal remit. In 2014–15, 819 cases were formally determined. In 2016–17, we expect to have determined around 1,600 cases.

And the age profile of our cases has drastically reduced. In 2015–16, only 59% of cases were determined within 12 months; in 2016–17, it was 96%.

We have begun seeking customer feedback on closed cases, every two weeks. In 2015–16, 88% of our customers felt that we treated them well (see box). In 2017–18, we expect this figure to be even higher.

‘The service was very helpful at every opportunity. From when I called to the end of service and I thank you for everything you have done in order to make the complaint go as smoothly and eÿciently as possible.’

‘It’s good to know that a final response isn’t necessarily final if you believe you have been treated badly.’

‘I felt my complaint was taken seriously and I was kept updated regularly of any changes that occurred. Information was gathered clearly and I was offered alternative ways to resolve my issue.’

‘Staff were very helpful and it was a relief to feel that my complaint was finally being taken seriously.’

I am very proud to have played my part in the HOS’s inspiring story. While I am going on to a new role, I am sure that the team will continue to provide an excellent service to customers.

- For further information or advice on the HOS, visit: www.housing-ombudsman.org.uk or telephone: 0300 111 3000