Cover story

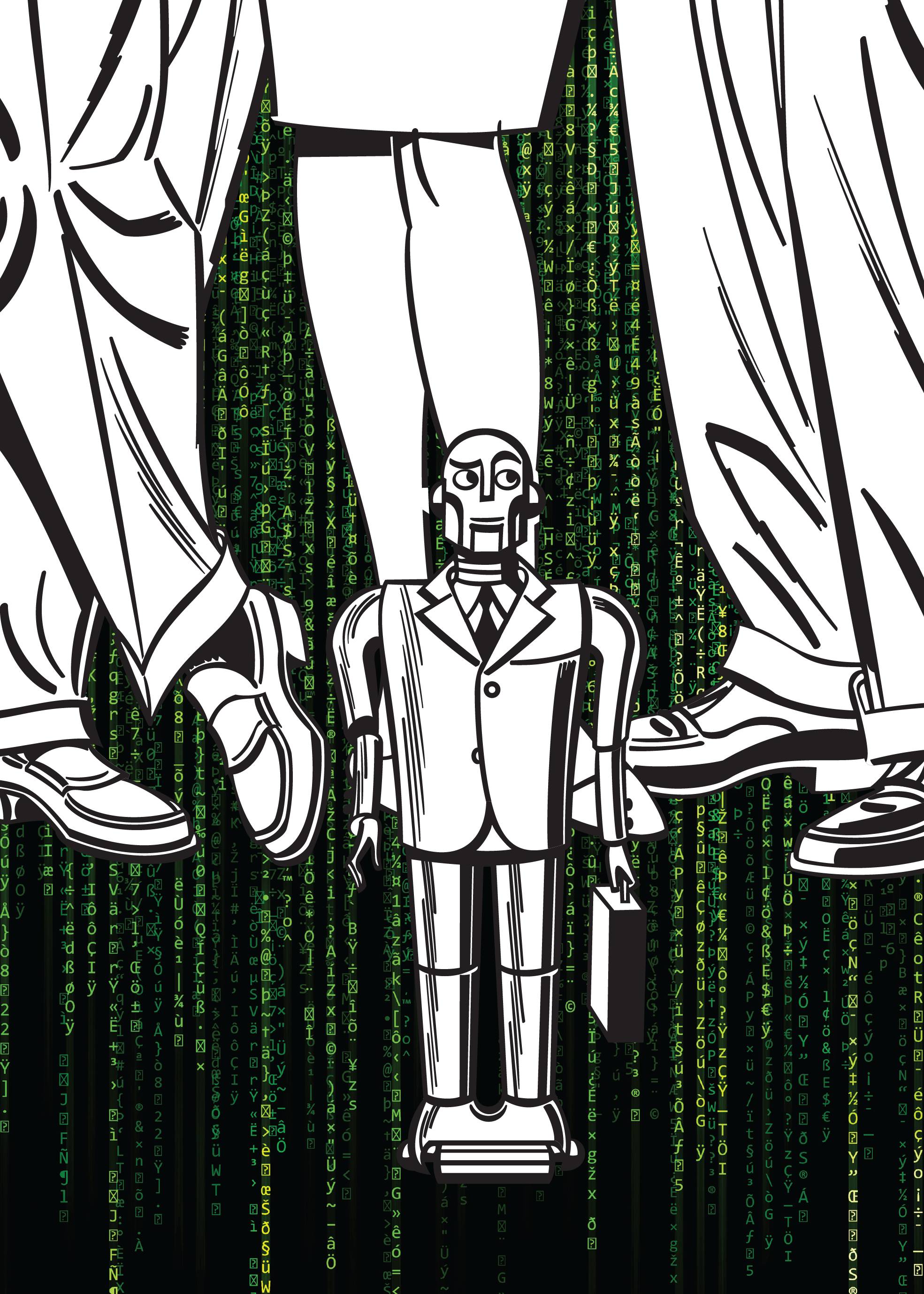

‘Virtual lawyers’: rise of the machines?

Catherine Baksi discusses the impact of robots and artificial intelligence (AI) on legal professionals.

About the author

Catherine Baksi is a freelance legal affairs journalist

For some, a piece about the rapidly advancing world of legal IT should, perhaps, come with the same calming advice inscribed in ‘large friendly letters’ on Douglas Adams’s The hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy: ‘Don’t panic!’

While most firms probably cannot recall how they functioned without mainstream technology like computers, e-mail and practice-management and time-recording software, the concept of robots and AI doing lawyers’ work is a step too far, particularly given the dramatic predictions about its impact on the legal landscape.

Legal futurologist and author of The end of lawyers?: rethinking the nature of legal services, Professor Richard Susskind OBE, told a conference this year that the profession has five years to reinvent itself from being ‘world-class legal advisers to world-class legal technologists’ .1

The 2014 report, Civilisation 2030: the near future for law firms , by Jomati Consultants predicted that robots and AI will dominate the legal profession within 15 years and lead to the ‘structural collapse’ of law firms.2 Turning up the fear volume even further, Professor Stephen Hawking and Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft, have warned that, potentially, AI will be more dangerous than nuclear weapons, if not appropriately controlled.

So, what is this phenomenon that has such power to turn the world, as we know it, upside down? Greg Wildisen, international managing director of AI software for legal and compliance at Neota Logic, explains that AI is broadly making computers perform tasks which would otherwise be done by humans.

Chrissie Lightfoot, futurist and author of the Naked Lawyer series, splits AI into two types. ‘Narrow AI’ , which describes ‘a range of cognitive computing and machine learning where the machine learning can ... design algorithms requiring human coding and programming’ , and ‘Deep AI’ , where algorithms are created for the machine to ‘self-learn’ .

AI is already all around: in smartphone voice recognition systems like Siri and Google Now; via online customer support; and behind driverless cars. As long ago as 1996, Deep Blue, the chess-playing , super-computer developed by IBM, defeated world chess champion Gary Kasparov, and earlier this year the AlphaGo programme by DeepMind, the Google-owned company, beat master Go player Lee Se-dol .

In the legal industry, the key technology, says Greg Wildisen, is ‘expert systems’ that use advanced computer processing and text-based analytics to analyse large volumes of information to answer specific questions. Examples that have hit the headlines have been IBM’s Watson. Its website explains that IBM Watson is a ‘technology platform that uses natural language processing and machine learning to reveal insights from large amounts of unstructured data’ . It is, says Greg Wildisen, a ‘search engine on speed’ , and is able to read masses of data to find information, making legal research quicker.

IBM’s Ross, which is billed as the ‘world’s first artificially intelligent attorney’ , is built on the Watson cognitive computer technology. It understands questions posed in natural language, ie, as a lawyer might ask their colleague: ‘Can a bankrupt company still conduct business?’, and reads through billions of text documents in seconds to provide an answer, with citations and suggested further reading. Ross also monitors developments in the law and improves the more it is used.

RAVN’s cognitive computing technology made a dataprocessing robot, ie, an Applied Cognitive Engine - RAVN ACE. It uses AI to search, read, interpret and summarise vast amounts of data 10 million times faster than a human.

A new kid on the block is Neota Logic. Greg Wildisen describes it as a ‘second-generation expert system’ , which uses intelligent software that combines rules, reasoning and judgment to answer legal questions. He explains: ‘We work with experts who put the rules and weighting factors into the system, which then gives the same answer as a lawyer.’

Market pressures and client demand for faster, cheaper and more accessible advice are forcing firms to look at innovative and creative ways to provide more for less. Technology provides a method to achieve this and, for those ahead of the curve, to differentiate themselves from their competitors – at least, until they catch up.

Expert systems, smart cognitive computing, AI and robot automation technologies, says Chrissie Lightfoot, can support firms with four key elements of legal service provision: commoditisation; research; reasoning; and judgment.

Some firms are showing increasing levels of interest in technology, which is reflected in the growing prevalence of techie job titles within them. But, says Chrissie Lightfoot, only a handful have really begun to take it up.

London firm Hodge Jones & Allen worked with academics from University College London to create software that assesses the merits of personal injury cases. In the City, Berwin Leighton Paisner, in conjunction with RAVN, developed LONald, a contract robot, to help it search Land Registry data in order to issue light obstruction notices; Linklaters developed Verify to check client names for banks; Pinsent Masons’ TechFrame system helps lawyers to read and analyse clauses in loan agreements; and US firm BakerHostetler uses Ross in its bankruptcy practice.

Neota Logic’s platform is being used by Anglo-German firm Taylor Wessing to assist with governance requirements, and in the USA for human resources compliance. For example, says Greg Wildisen: ‘You can ask about the classification of employees. In the US, there are 50 states with federal and local employment laws. Lawyers have put 1,300 cases and 80 weighting factors into the system, which can tell you if someone is an employee.’

Neota Logic is also working with American universities to develop smart apps to help legal advice charities. Chrissie Lightfoot predicts that the use of AI will accelerate over the coming months, ‘as the chasing legal pack’ is forced to follow the ‘first movers’ to reap the benefits and to remain competitive.

Predictive coding uses computer algorithms to review documents, and use of the technology has been backed by the High Court in two cases. In (1) Pyrrho Investments Ltd (2) MWB Business Exchange Ltd v (1) MWB Property Ltd (2) Aspland-Robinson (3) Pankhania (4) Balfour-Lynn (5) Singh [2016] EWHC 256 (Ch), the parties had agreed to its use but, in the light of its relatively recent introduction into English litigation, sought judicial approval for its use.

Master Matthews duly gave his approval, listing 10 reasons why it was appropriate, including the number of documents to be reviewed; the predicted costs savings; and size of the claim.

In the first contested use of predictive coding, boutique firm Candey challenged its use by BLP and expressed anxiety over its accuracy. In Brown v BCA Trading (2016) 17 May (Ch), the high court permitted its use and approved the factors set out earlier in the year in Pyrrho Investments Ltd above.

Innovative practice Riverview Law is working with Liverpool University to see the extent to which AI can be used in the law. It has set up a separate technology arm to sell its products, including its new virtual assistant, Kim (see box).

An emerging trend among technophile law firms is the hackathon, where computer wizards collaborate to find IT solutions. In March, law website ‘Legal Geek’ hosted Europe’s first Law Tech charity hackathon, at Google’s Campus London, where teams worked to develop IT solutions to support Hackney Community Law Centre®. On the same weekend, the Ministry of Justice held a similar event, ‘Hacking justice: data in the dock’ , to see how technology could improve efficiency in the courts, improve rehabilitation to offenders and reduce risk to the legal aid fund.

‘No’ , says Karl Chapman, ‘but failure to adopt technology will be the death of many.’ There will, he says, always be professionals dispensing legal advice, just fewer than today.

As machines become more intelligent and lawyers become more comfortable using them, Chrissie Lightfoot predicts that machines will switch from ‘carthorse to racehorse’ and enable or replace more legal roles.

Richard Susskind expects this to happen to such an extent that, by 2020, AI systems will be able to diagnose and respond to clients’ legal problems so that lawyers are ‘no longer face-to-face advisers’ , but ‘a person putting in systems and processes’ .

But it is not all doom and gloom. Greg Wildisen says that AI is not aiming to threaten the role of lawyers, but to enhance it. It could, he says, be an opportunity to fill the justice gap and provide advice to the growing number of people who cannot afford a lawyer.

So, perhaps AI should be seen more like Samantha, the obliging computer-operating system personified by Scarlett Johansson’s voice in the 2013 drama/romance film ‘Her’ , than the menacing artificial general intelligence, Hal 9000, in Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: a space odyssey’ .

Karl Chapman, chief executive of Riverview Law, introduces Kim

What is Kim?

Kim stands for knowledge, intelligence, meaning. Knowledge is pervasive, intelligence requires meaning and context to be effective and Kim provides all three.

What is a ‘virtual assistant’?

For businesses, it helps knowledge workers make better, quicker decisions.3 It is a real-time tool that provides knowledge, intelligence and meaning to users to improve processes, support decision-making and propose answers. For consumers, they are tools that help them live more easily, like Uber and Airbnb.

What is the technology?

Our virtual assistants are built on our Kim technology platform to automate data, documents, processes and workflows quickly. Kim does this on-demand and with no programming. In essence, it is a virtual software developer AI that captures knowledge workers’ intelligence and meaning, and drives dynamic case management with variable structured data. Who developed Kim? We acquired a US technology company called CliXLEX in September 2015 and renamed it Kim.

What does it do?

We have three levels of virtual assistant: process; advisory; and smart assistants. Process assistants help businesses and people to manage activity; advisory assistants support professionals in a single topic area, for instance, contract, litigation or employment; and smart assistants actively suggest solutions and answers.

For example, our instruction and triage assistants help in-house teams ensure that the right work is done by the right people, at the right price. They do this by managing instructions coming in, triaging them to the appropriate individual and automatically delivering real-time and trend dashboards and management information. They provide the foundational data layer on which in-house teams can build an effective legal operating model.

Is Kim better than a human?

Kim can do some things better than people. It can work processes, analyse data and propose solutions more quickly; it can scale globally; it never sleeps; and is always ready to help.

However, there are things that people can - for now - do better than Kim. People can exercise judgment differently to the way computers do, which should not be underestimated.

Will it replace lawyers?

There will always be a need for lawyers, but they will need to adapt to a radically changing world where the role they play in the legal system evolves dramatically. Over the next 20 years, knowledge will become more widely available. In-house teams will have tools to do much of the work previously undertaken by law firms. Driven by customers, law firms will change the services they deliver them. Over time, the best bet is that there will be fewer lawyers doing higher value work.

What will consumers think?

Customers - whether individuals, businesses or government - want solutions. Like all technology, from the wheel to AI, if it solves the problem, it will be accepted. If it’s easier to use an ATM or online banking, they will use it. If it’s better to use Uber than stand on a sidewalk and hope to flag a taxi, they will use the app. Over the long term, resistance is futile.

Will consumers expect lower fees?

Let’s hope legal advice becomes more cost-e ffective. The legal market has no great track-record in making access to justice widely available. Even global corporations have grown the size of their in-house functions because it’s cheaper to employ lawyers than use law firms. What supply chain creates a situation where it is cheaper for customers to do it themselves? For all our sakes, let’s hope technology drives change!

1 Richard Susskind presented ‘The future of professional services’ at the Law Society’s law management section annual conference in April 2016

2 For a copy of the report, e-mail : tony.williams@jomati.com

3 A knowledge worker is a person whose job involves handling or using information.