Constructive trusts

Abigail Jackson examines how constructive trusts arise and how the courts deal with equitable interests.

About the author

Abigail Jackson is a solicitor and a lecturer in law at the University of East London.

This article examines how constructive trusts arise and the way in which equitable interests are dealt with by the courts

In a busy family practice, it is common for lawyers to advise clients on whether they have a claim for a share of the family home in the event of a relationship breakdown. For clients that are married or living with a civil partner, those rights are governed by the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 and the Civil Partnerships Act 2004.

However, where couples are simply co-habiting, any entitlement to a share in the family home is determined by the law on common intention constructive trusts. Against that background, this article examines how constructive trusts arise and the way in which equitable interests are dealt with by the courts.

Before considering the law, it is worth noting that constructive trusts only arise where there is a dispute over the parties’ shared home. If friends or family members buy an investment property together, this will be governed by a resulting trust analysis, which is outside the scope of this article (see, for example, Laskar v Laskar [2008] EWCA Civ 347; [2008] 2 EGLR 70).

From the judgment in Stack v Dowden [2007] UKHL 17, it appeared initially that constructive trusts would only arise where there was a dispute between co-habiting couples. Nevertheless, more recently, the Court of Appeal has taken a broader approach. The appeal court held that a constructive trust arose between two flatsharers, who bought a property together (Gallarotti v Sebastianelli [2012] EWCA Civ 865). As a result, we may find that there are an increasing number of cases before the courts involving friends and siblings.

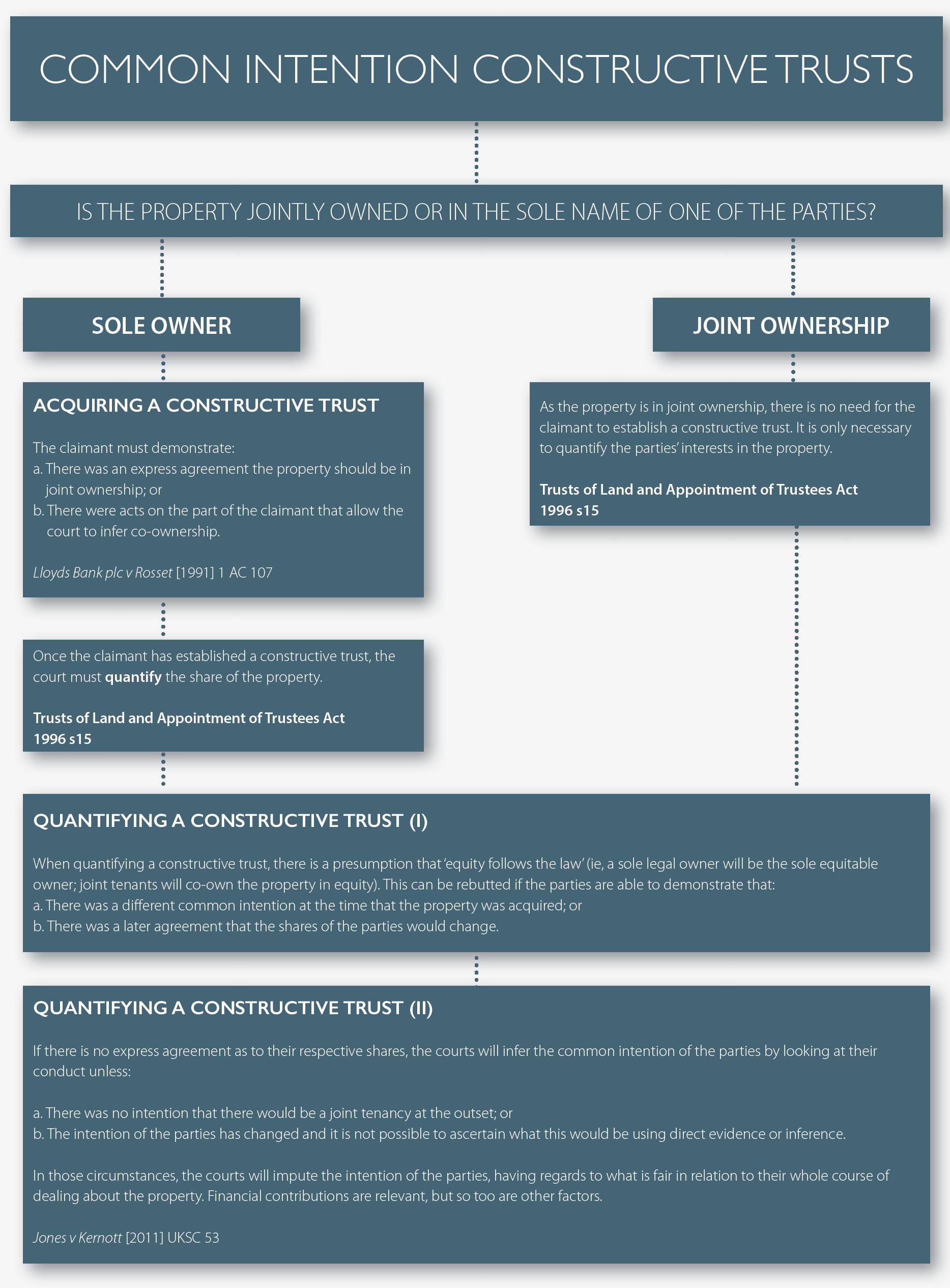

Put simply, constructive trusts can arise where the legal title to the family home is either owned by one individual or by a couple in their joint names. In Jones v Kernott [2011] UKSC 53, the Supreme Court held that the lower courts should approach those cases differently. Following that guidance, this article will consider how a constructive trust can arise where there is only one legal owner of the family home, before addressing the principles that apply to joint tenancies.

If one individual owns the legal title to the family home, the other party must prove that they have acquired a beneficial interest in the property. Usually this involves the claimant demonstrating that it is ‘unconscionable’ that they be denied a share in the family home in the manner set out in Lloyds Bank plc v Rosset and another [1991] UKHL 14.

Mr and Mrs Rosset bought a dilapidated farmhouse in Mr Rosset’s sole name. Although Mrs Rosset did not contribute financially to the purchase, she assisted with the renovation work and supervised builders. However, without Mrs Rosset’s knowledge, Mr Rosset took out a mortgage on the property and failed to make any repayments to the bank. Subsequently, the bank sought possession of the farmhouse.

To prevent the bank from repossessing the property, Mrs Rosset claimed that she had an overriding interest in the farmhouse under Land Registration Act 1925 s70(1)( g) by virtue of having an equitable interest in the land and being in actual occupation. As a result, the question arose about whether Mrs Rosset’s conduct was sufficient to create a constructive trust. In Rosset, Lord Bridge held that a constructive trust would arise if:

- there was an express common intention that the couple would share the equitable ownership of the property; or

- there was an inferred common intention, based on the conduct of the claimant acting to his or her detriment.

When Lord Bridge identified the requirement for an express common intention, he gave two ‘excuse’ cases as examples of where there was the necessary agreement. More specifically, he cited Eves v Eves [1975] 1 WLR 1338, in which the defendant told his girlfriend she was too young to be a registered owner of the property. He also referred to Grant v Edwards [1986] 3 WLR 114, where the male partner said that the house should be registered in his sole name as it could affect his girlfriend’s divorce proceedings.

According to Lord Bridge, these cases demonstrate that there is an express common intention because the family home would have been registered in the couple’s joint names, but for the excuse of one of the partners. Put simply, one partner is attempting to avoid the property being registered in the couple’s joint names even though there was an agreement to the contrary.

Once a claimant has established that there was an express common intention, they will need to show detrimental reliance. In other words, the claimant has acted in such a manner, relying on the fact that they owned a share in the property. So, for example, in Eves above Lord Denning emphasised that the female partner had renovated the garden with a sledgehammer while she was pregnant with the couple’s second child. Meanwhile, in Grant v Edwards the female partner paid a significant amount towards the household expenses and looked after the children. For Lord Bridge, as long as the contribution was significant as opposed to de minimis, it would be sufficient to establish a constructive trust.

Stack v Dowden

[2007] UKHL 17

After starting a relationship in 1975, Ms Stack and Mr Dowden decided to live together in a property that was owned by Ms Stack and registered in her name. Several years later, they decided to buy a home together as joint tenants. Although Ms Stack contributed most of the money for the purchase, the couple took out a joint mortgage to which they both contributed.

In 2002, Ms Stack and Mr Dowden separated, with Mr Dowden seeking an order that he should be awarded a 50% share in the family home. This was granted by a district judge at first instance. The decision was overturned by the Court of Appeal, which awarded Ms Stack a 65% share of the property.

The case continued to the House of Lords, where Baroness Hale emphasised that the starting point for co-ownership disputes was that the presumption that the property was owned in equal shares. That presumption could be overturned, but only in unusual cases. It was not suÿcient for the parties simply to demonstrate that they contributed to the purchase price in unequal shares. Rather, the court should infer the intention of the parties by looking at the following:

- Any discussions at the time of transfer of the property.

- The purpose for which the house was acquired and how it was financed.

- The nature of the relationship between the parties.

- How the couple arranged their finances and other outgoings.

- The parties’ individual characters and personalities.

According to Lord Bridge in Rosset above, it is possible for the courts to infer a common intention that a couple would jointly own the family home. However, they should only do so if the claimant made a direct financial contribution to the purchase price. Since a financial contribution is enough to establish detrimental reliance, there is nothing further that a claimant needs to demonstrate.

Nevertheless, there is some doubt over whether this principle is still good law, with Baroness Hale commenting obiter in Stack above that Lord Bridge may have set the bar ‘rather too high in certain respects’. Similarly, in a first instance decision in LeFoe v LeFoe [2001] 2 FLR 970, the judge held that indirect financial contributions, such as payments towards the mortgage, could allow the court to infer a common intention that the ownership of the property would be shared.

With co-ownership disputes, the first stage is for the court to consider whether the presumption of equitable joint ownership can be rebutted. This would involve reviewing the factors set out by Baroness Hale in Stack to see whether this can be inferred (see Jones above).

For CILEx Level 3 examinations, there may be a short question on constructive trusts or, alternatively, the topic could form part of a longer problem question. At CILEx Level 6, constructive trusts could be examined with either an essay or a problem question.

When you are answering a problem question, remember to identify the legal owner of the property, as this will have an effect on how the courts deals with the case. After all, the starting point for co-ownership disputes is the maxim that ‘equity follows the law’.

For cases involving a sole owner, you will need to set out the criteria for establishing a constructive trust in Rosset, before explaining whether these are met by the facts in the question.

- Was there an agreement that the parties would own the property jointly?

- Did one person make an ‘excuse’ about why the other should not be named on the title deeds?

Once a claimant has established a constructive trust or rebutted the presumption of equitable joint ownership, the court is required to determine the party’s share of the property under Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996 s15. If there is no express agreement, the courts will review the parties’ conduct to determine whether any inference can be drawn about their respective shares (Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886).

However, if this is not possible, the courts may impute the intention of the parties by considering the whole course of dealings between the parties in relation to the property and having regard to what is fair in those circumstances (Oxley v Hiscock [2004] EWCA Civ 546; [2004] 3 WLR 715). In Oxley, Chadwick LJ accepted that this could involve looking at non- financial contributions to the household, such as looking after children and carrying out DIY.

Despite the decision in Oxley and its subsequent approval in Jones above, later cases have taken a restrictive approach to determining a party’s share in the property. In practice, the courts have preferred to rely on financial contributions to the property, as opposed to a wider range of factors. For example, in Supperstone v Hurst and Hurst [2005] EWHC 1309 (Ch), the judge indicated that it was outside his remit to make an order based on indirect financial contributions. Likewise, in Graham-York v (1) Adrian York (personal representative of the estate of Norton Brian York) and others (2) Leeds Building Society [2015] EWCA Civ 72, the Court of Appeal failed to take account of a couple’s abusive relationship in determining their respective shares in the property.

So, to conclude, while a Chartered Legal Executive may refer the court to a range of factors that affect a claimant’s share in the family home, the likelihood is that this will be determined by both direct and indirect financial contributions to the purchase price.

Once you have established that there is a constructive trust, you should address the issue of quantification. In other words, what share of the property is a claimant likely to receive?

Students often forget to comment on quantification in sufficient detail with sole-ownership cases, and this can be an area where they lose marks. Moving on to co-ownership disputes, think about whether the equitable presumption can be rebutted. Are there any good reasons why a party’s beneficial interest in the property should not reflect the legal ownership of the land? Here, you should refer to the judgments in Stack and in Jones. The best answers are likely to

Moving on to co-ownership disputes, think about whether the equitable presumption can be rebutted. Are there any good reasons why a party’s beneficial interest in the property should not reflect the legal ownership of the land? Here, you should refer to the judgments in Stack and in Jones.

The best answers are likely to analyse Lady Hale’s five-stage test in Jones for quantifying equitable interests in a jointly owned home before discussing the difference between inferring and imputing intention.*

- David Cowan, Lorna Fox O'Mahony and Neil Cobb, Great debates in land law, 2nd edn, 2016, Palgrave MacMillan.

- Ben McFarlane, Nicholas Hopkins, and Sarah Nield (2015) Land law: text, cases, and materials, 3rd edn, OUP.

- Brian Sloan, (2015), ‘Keeping up with the Jones case: establishing constructive trusts in ‘sole legal owner’ scenarios’, Legal Studies (Soc Leg Scholars), 35: 226–251.

- Anna Lawson, (1996), ‘The things we do for love: detrimental reliance in the family home’, Legal Studies, 16: 218–231.

- Lorna Fox O’Mahony, ‘Property Outsiders and the Hidden Politics of Doctrinalism’, Current Legal Problems, (2014) Vol 67(1), pp409–445.