Comment

‘Helping women through the law’

Emma Scott and Olivia Piercy discuss the 40-year ‘herstory’ of Rights of Women.

Rights of Women is a charity perhaps best known for providing free legal advice to women through our telephone advice lines and for publishing legal guides and DIY handbooks to help women navigate their way through the law. These are the core services we have been delivering since we formed as a collective of women lawyers in 1975. They are services which are increasingly in demand and, in the wake of devastating cuts to legal aid, for countless women provide the only legal assistance they can hope to receive.

As one might expect of an organisation born of the women’s liberation movement, Rights of Women has at its core a strong campaigning vein; anchored in the experiences of the women who contact us and through academic research, we have led and been involved in campaigns which have resulted in some of the most significant advances in women’s legal rights in England and Wales over the last four decades. As Rights of Women turned 40 this year, it seems a fitting moment to take stock of our achievements so far, and to galvanise for the challenges ahead.

Rights of Women was formed in 1975 by a group of women legal workers as a direct response to the fifth demand of the women’s liberation movement for legal and financial independence for women. To put this in context, 1975 was the year that the Equal Pay Act came into force and the Sex Discrimination Act was passed and our primary focus in those early days was to address the debilitating economic inequality faced by women. As the only feminist legal project in the UK at the time, we networked with feminist lawyers and activists nationally and internationally.

In the late 1970s, we formed the YBA wife? (Why be a wife?) campaign aimed at raising awareness of the discrimination faced by married women. At that time, married women were unable even to claim social security benefits in their own right. We lobbied for individually based benefits; the abolition of the married man’s tax allowance; dependency increases to be paid to married women; and occupational pension rights on divorce.

We protested outside the then Department of Health and Social Security, and famously, in 1984, our members presented a stale loaf of bread to the secretary of state with the message: ‘We are fed up with being fobbed off with crumbs from under men’s tables – we want an independent income for women.’

Much of what we campaigned for has since been achieved. Through the passing of the Social Security Act in 1990, access to supplementary benefits no longer depends on sex or marital status. The Welfare Reform and Pensions Act came into force in 1999, allowing occupational and personal pensions to be shared between couples on divorce, and the married man’s tax allowance was eventually abolished in 2000.

Another primary focus of Rights of Women’s efforts in the early years was tackling the discrimination of lesbian mothers in the family courts. In 1982, our lesbian custody group provided support for lesbian mothers who experienced prejudice in the courts. Our research, Lesbian mothers on trial, in 1984, found that lesbian mothers faced stark prejudice and an assumption that they were unfit parents in whose care children would experience harm. The report exposed this discrimination at all institutional levels within the judiciary, among welfare officers and throughout the legal profession.

Rights of Women sought to address the issue by training family lawyers on how to represent lesbian mothers in child custody cases and, in 1986, our research was incorporated into a book, Lesbian Mothers’ Legal Handbook. The book included a critique of the law, and provided strategic advice to lesbian mothers for dealing with lawyers and court welfare oÿcers . As a result of the work of the Lesbian Custody Group and the wider feminist movement, the case-law began to change in the late 1980s. Although levels of prejudice experienced in the courts were still unacceptable, increasingly lesbian mothers were being granted custody of their children. A new statutory framework introduced by the Civil Partnership Act 2004 and the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 have helped to enforce a legal recognition and respect for same-sex families.

In more recent years, through listening to the concerns of the women who call our advice lines, our efforts as an organisation have turned increasingly to addressing the epidemic of violence against women. Our achievements in this area, and the advances of the women’s movement in general, are not insignificant. We have fiercely and successfully campaigned for the criminalisation of marital rape (1991); for the ‘battered wives’ partial defence to murder (1992 and 1995 respectively); for the introduction of a clear legal framework for civil protection from domestic violence (1996); and for the criminalisation of paying for sex with someone who is controlled for gain (2009).

In 2005, we assisted in the drafting of new civil remedies for forced marriage, which were enshrined in law in 2007 in the form of forced marriage protection orders under the Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007. Following our unsuccessful opposition to the unhelpful criminalisation of forced marriage in 2014, we have been undertaking extensive research to expose and highlight the ongoing legal and institutional failures in the treatment of this complex form of abuse.1 1

In spite of the marked improvements to the legal frameworks, the issue of violence against women and girls can feel to us, in the women’s sector, both immutable and insurmountable. Through our own research, we found that the family law legal aid cuts, introduced in 2012 with their callously restrictive domestic violence evidence criteria, have left 40% of survivors of domestic violence unable to evidence that violence for the purposes of legal aid.2 2 Each year, hundreds of thousands of women who call our legal advice lines are unable to get through. Predominantly, our callers have experienced or are still experiencing ongoing domestic violence, and they are, for the most part, unable to access any form of legal representation or support. In conjunction with the cuts to benefits and housing, these women often cannot financially afford to leave their situations, there are fewer and fewer refuge spaces and they have nowhere to go.

So, what do we do now and how do we rally in the face of such challenges? We keep going; we listen to the voices of the women who seek our support; and we adapt. Rights of Women continues to produce accessible legal guides and handbooks. Most recently, we published Child arrangements and domestic violence: a handbook for women, a comprehensive guide designed to help women navigate their own way through private children law proceedings.3 3

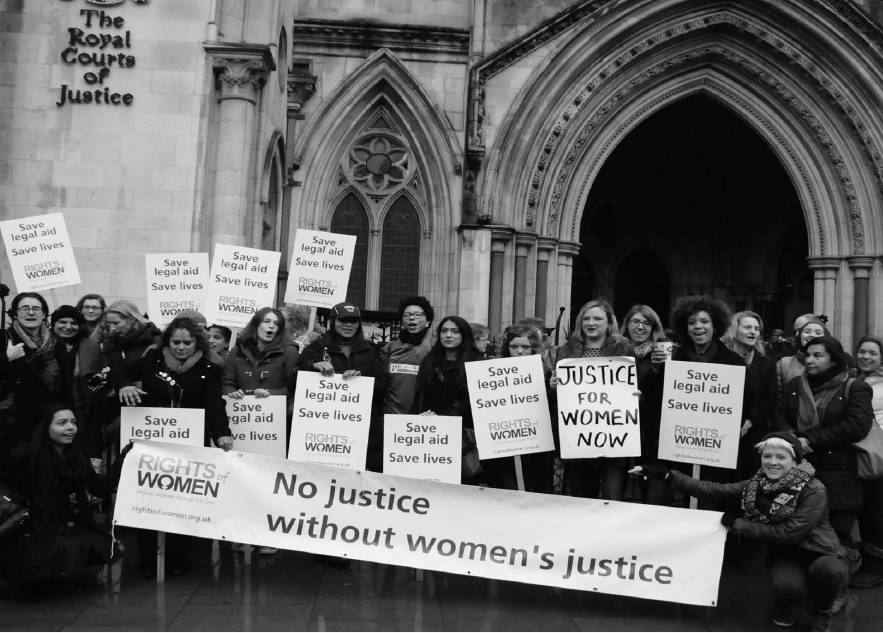

We continue to train professionals, equipping them with vital skills and knowledge so that, in turn, they can better support the women with whom they work. We have identified the particular needs of vulnerable migrant women experiencing violence, and we have extended our services to support and advise those women. We continue to campaign to ensure that women’s voices are heard and that law and policy meet women’s needs. And finally, having launched (and lost) a judicial review against the domestic violence evidence criteria for legal aid (R (Rights of Women) v Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice [2015] EWHC 35 (Admin)) we have sought and been granted permission to appeal in January 2016.

We know from past campaigns that sometimes change takes decades. We are keenly aware that women’s need for our free legal advice and information is, perhaps, now greater than before. While women remain unequal in our justice systems, Rights of Women remains committed to continuing to do what we can to help women through the law.

- For more information about our work and our anniversary, visit: www.rightsofwomen.org.uk

1 ‘This is not my destiny.’ Reflecting on responses to forced marriage in England and Wales, Imkaan and Rights of Women, 2014, available here

2 Evidencing domestic violence: a year on, Rights of Women, 2014

3 To order, visit here