Government

Odds-on for an early general election?

Neil Parpworth discusses the likelihood of an early election (before 2020) and how this could be brought about under the provisions of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act (FtPA) 2011.

About the author

Neil Parpworth is principal lecturer in law at Leicester De Montfort Law School.

F ollowing the outcome of the EU referendum, which saw the ‘leave’ vote triumph over the ‘remain’ vote by a majority of nearly 1.27 million, David Cameron, the then prime minister, announced his intention to resign so that a new leader of the Conservative party could be elected in order to take forward the UK’s EU withdrawal negotiations (see also page 20 of this issue). As it turned out, the former Home Secretary, Theresa May, emerged as the new leader rather more quickly than had been anticipated after her rivals were either defeated or withdrew from the election contest.

The change at the top has, therefore, occurred without a general election; however, this is by no means unprecedented. Thus, in the past 25 or so years, two prime ministers, John Major and Gordon Brown, succeeded to the office during the lifetime of a parliament. Their fates at the next general election were, however, rather different. While, against the odds, John Major won in 1992, the Labour party, under Gordon Brown, failed to obtain a majority in the 2010 general election and this resulted in the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government.

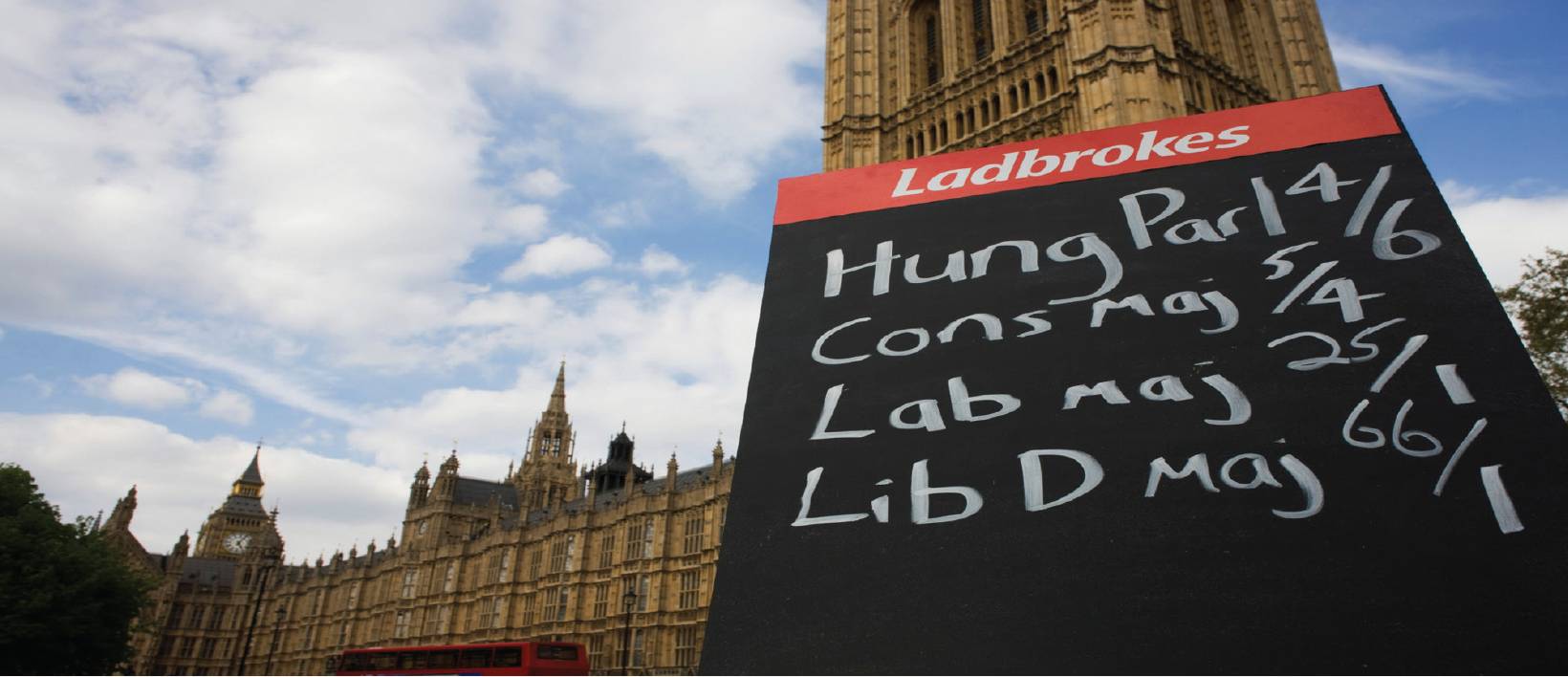

At the time of writing, a leading bookmaker was offering odds about when the next general election will be held: a date in May 2020 is 4/9, whereas general elections in either 2016 or 2017 are 5/2. For the uninitiated, this indicates that in the opinion of the bookmaker (and punters), the present parliament is most likely to last the full five years as specified in the FtPA. It also indicates, however, that an earlier general election is a distinct possibility. If this were to happen, the mechanisms for bringing it about would be those provided for under the FtPA rather than the traditional means. The differences between the old and the new arrangements merit consideration.

Before the FtPA, general elections occurred, by and large, when the party in government wanted them to. The prime minister would request that the monarch use the prerogative power to dissolve parliament, and the request would be granted. Occasionally, the prime minister’s hand would be forced because the five-year maximum life of a parliament loomed (as specified under the Parliament Act 1911), or because a motion of ‘no confidence’ had been passed against the government, as happened on 28 March 1979 when James Callaghan’s Labour government was defeated by 311 to 310 votes. Generally speaking, however, the timing of an election was at the discretion of the government, and the decision to ‘go to the country’ was likely to be taken when it was felt politically advantageous to do so.

Under the FtPA, the norm will become something different. Ordinarily, general elections will take place five years after the last election. This is what happened in 2015, and it is why the next general election is scheduled to take place in 2020. Of course, an election every five years may not always be in the best interests of the country.

Accordingly, the FtPA allows for the possibility of an early general election in either of two circumstances. The first relates to the passing of a motion ‘[ t]hat there shall be an early parliamentary general election’ (FtPA s2(1)( a) and (2)) . Where such a motion is passed by at least two-thirds of the number of seats in the House of Commons (on present numbers, around 434 MPs), a general election will follow. In the second circumstance, an early general election could also be held if the Commons were to pass a motion ‘[ t]hat this House has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government’ (FtPA s2(3)( a) and (4)) . Unlike the early general election motion, there is no specified majority required in respect of a ‘no confidence’ motion. Therefore, it could be passed by a simple majority of the MPs who walked through the division lobbies. If this were to happen, a general election need not necessarily follow since there is a period of 14 days following the passage of the motion, during which the House of Commons could pass a further motion that it has ‘confidence in Her Majesty’s Government’ . Thus, if there is parliamentary support for an alternative government, an early general election need not take place.

The new prime minister has much to do following the formation of her government, including playing a central role in the UK’s EU withdrawal negotiations. Although there is no obligation for her to seek an early general election, she may decide that her government ought to be elected on the basis of its own mandate rather than that inherited from the Cameron government. In addition, it might be thought that her government will have greater legitimacy as a result of having won an election.

Also, of course, the present disarray within the Labour party may enter into calculations. If an early election is considered desirable, it could be secured by using either of the mechanisms set down in the FtPA and described above. The two-thirds majority required for the motion in favour of an election may make it the less attractive option, since it would require crossparty support to be passed. Since the Labour party has 229 seats in the House of Commons currently, it has a substantial blocking vote. If the leadership did not support an early general election and it was able to get Labour MPs to vote accordingly, the section 2(1)( a) and (2) trigger would not be activated.

Thus, if Theresa May wishes there to be a general election later this year, her best option would be to table a motion of ‘no confidence’ in her own government. Assuming that all 330 Conservative MPs voted in favour, it would achieve the simple majority for the motion to be passed and parliament would be dissolved in keeping with FtPA s3(1).

It remains to be seen what the new prime minister will do regarding the issue under discussion. Under the old arrangements, the monarch’s consent to the dissolution of parliament would have been easily obtained, especially because of the seismic change of circumstances occasioned by the EU referendum outcome. It will be advisable for Theresa May to be decisive on this issue, since few are likely to forget how Gordon Brown’s failure to seek an early general election during his own ‘honeymoon period’ after taking over from Tony Blair was, in all probability, a misjudgement which backfired on him later.

Given that a future prime minister will be under a duty, as a result of section 7(4), to make arrangements for a review of the FtPA to be carried out and published by late 2020 or early 2021, it would be interesting if the period under study consisted of something other than two full-term parliaments. Whether it does will, however, be the consequence of a decision taken by the new prime minister and her government. Patently, the longterm future of the FtPA will have no bearing whatsoever on that decision.