Study area

Joint enterprise liability: a fresh approach

Hannah Roberts examines R v Jogee [2016] UKSC 8, 18 February, concerning the intent that must be proved when a defendant is accused of being a secondary party to a crime.*

About the author

Hannah Roberts GCILEx is a freelance writer and a former law lecturer.

The Supreme Court judgment in R v Jogee was viewed as a landmark since the highest court in the land has ruled that this area of law had been incorrectly interpreted for 30 years. This will not only have a huge impact on cases in the future, but may also lead to appeals from those convicted under the ‘wrong’ law.

The case involved Jogee, whose friend Mohammed Hirsi fatally stabbed Paul Fyfe in the early hours of 10 June 2011. Both Jogee and Hirsi were intoxicated and aggressive when they arrived, late at night, at the home of Fyfe’s girlfriend. After a variety of to-ing and fro-ing , and threats and arguments, Hirsi gained entry to the house and angrily confronted Fyfe, while Jogee remained outside shouting at his companion to do something to Fyfe. Jogee appeared at the doorway at one point, armed with a brandy bottle and expressed the desire to smash it over Fyfe’s head, but the victim was too far away. Soon after this, Hirsi stabbed Fyfe in the chest before running off with Jogee. Fyfe died at the scene.

Both men were convicted of Fyfe’s murder, in March 2012, at Nottingham Crown Court. In July 2013, the Court of Appeal upheld Jogee’s conviction, with the trial judge ruled as having correctly interpreted the law on joint enterprise as it then stood ([ 2013] EWCA Crim 1433).

The law on joint enterprise sits within secondary participation, which is where an individual encourages or assists the principal offender in some way. The principal is, of course, the person who performs the actus reus, ie, the person who fires the gun, inflicts the fatal stab wound, or who steals the property.

To establish secondary participation, an individual must be shown to have aided, abetted, counselled or procured the commission of the offence by the principal. This is the actus reus of the secondary party’s crime. While there will often be an agreement in place between the principal and the secondary party, this need not always be so.

The secondary party must also have an intention to assist or encourage the principal’s commission of the offence, with the necessary mens rea, ie, knowing that the principal’s actions constitute a crime. In other words, liability as a secondary party is established via proof of intentional assistance or encouragement.

If this can be shown, the secondary party will be convicted and sentenced as if they had been the principal. This means that, for example, ‘merely’ driving a getaway car after a bank robbery will land an individual in just as much trouble as if they had pulled on a balaclava and brandished the sawn-o ff shotgun themselves.

Joint enterprise (sometimes alternatively called parasitic accessory liability or collateral liability), however, involves a specific set of circumstances, ie, two or more individuals set out together, engaged on some ‘common criminal purpose’ , where one of them ends up committing a further offence. A typical example would be where D1 and D2 set out to rob X. D2 knows that D1 has armed themself with a gun and that D1 has violent tendencies. During the course of the robbery (crime A), X puts up a fight. D1 pulls out the gun and shoots X dead (crime B).

Before Jogee, there were two leading cases on joint enterprise: Chan Wing-Siu v the Queen [1985] AC 168 and R v Powell and another; R v English [1999] 1 AC 1. The leading cases stated that D2’s liability in such a situation would be established if it could be shown that, having foreseen crime B as a possibility, D2 continued to participate in the undertaking.

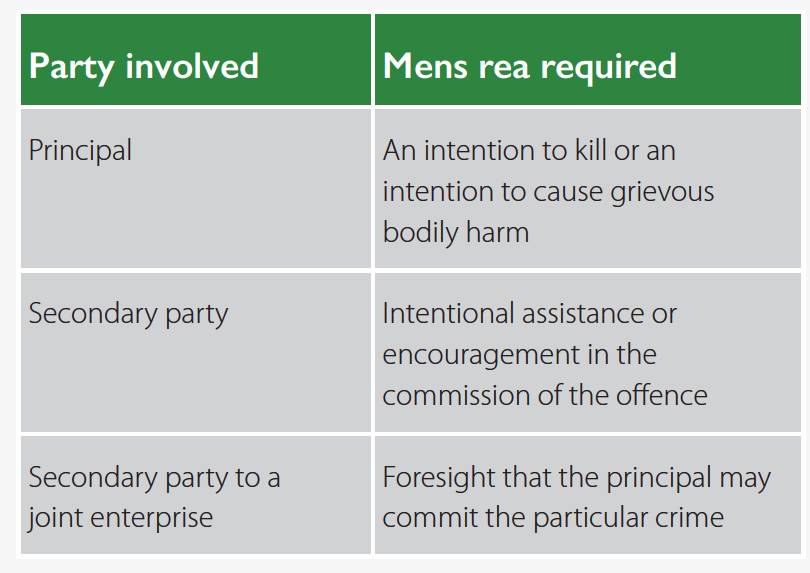

These decisions were somewhat controversial, as effectively they confirmed joint enterprise as a subcategory of secondary participation, with different rules applying. Furthermore, the mens rea requirement for the secondary party in a joint enterprise was much lower than it was for the principal and, indeed, for a secondary party in a non-joint-enterprise situation; yet, all parties would be convicted and sentenced equally. For example, with regard to murder, see the table below.

The then House of Lords’ judges in Powell and English felt that their decision was based on a ‘strong line of authority’ (per Lord Hutton at Powell and English p18, and per Lords Hughes and Toulson at Jogee para 53). Their Lordships also noted that there were policy considerations in place which justified setting the bar that much lower for the secondary party. These concerns were deliberated further in Jogee, and included the need to ensure that the law was properly able to protect the public from gangs.

Having undertaken a thorough examination of a wide range of relevant previous decisions, including the leading cases, the Supreme Court justices felt that, in Jogee, the law was in need of change and identified five key justifications for so doing:

- The leading cases failed to consider a sufficiently wide range of preceding authorities.

- The law in this area was not working well, causing difficulties for judges and giving rise to many appeals.

- With secondary liability being a key legal area, it was important that any error within it be corrected;

- It was not acceptable, following the enactment of Criminal Law Act 1967 s8 (as amended), to allow foresight to be used as mens rea for (in this case) murder.

- The anomaly of the secondary party requiring a lower mens rea than the principal was a conspicuous one. Other difficulties that the justices had with the leading cases included the following:

- A new doctrine (ie, separate rules for joint enterprise situations) had been unnecessarily introduced within secondary liability.

- The law in place before the leading cases was sufficient to ensure public protection from the consequences of gangs and violent crime.

The Supreme Court justices were also happy that this was not a legal area requiring parliamentary correction: the law on secondary participation has been developed by the courts, and it is therefore for the courts to correct any errors that have been made in that development. The key alterations made by the justices in Jogee to the law on joint enterprise can be summarised as follows:

- Foresight of consequences does not equate to intention; instead, it is merely evidence from which the jury could choose to infer intention (or not, as the case may be). In making this decision, the jury will need to consider all the relevant facts of the case.

- For D2 to be convicted of murder, it must be shown that they intended to assist D1 in the intentional infliction of death or serious bodily harm on the victim. This intention on the part of D1 could, of course, be conditional, ie, if it became necessary to do so. Either way, if this intention cannot be found, then D2 cannot be convicted of murder, although they may well be liable instead for (constructive or unlawful act) manslaughter.

Consequently, Jogee’s conviction for murder was set aside as the law had been wrongly stated at his trial and appeal. The unanimous conclusion of the court is that the leading cases took a ‘wrong turn’ . The prosecution and defence are submitting written submissions about whether Jogee should now face a retrial for murder or, instead, have the verdict replaced by a manslaughter conviction.

The court is not expecting a huge wave of appeals from those already convicted in similar cases. Exceptional leave must first be sought from the Court of Appeal, but this will not be granted simply because the law has been declared wrong. Furthermore, in many of those cases, the point now clarified is unlikely to have been crucial.

In terms of the future, even though it may now be a little trickier to secure a murder conviction in a joint enterprise situation, an alternative conviction for manslaughter will often be relatively straightforward to achieve, and judges retain the right to impose up to life imprisonment for such crimes.

* R v Jogee [2016] UKSC 8 was heard at the same time as Ruddock v the Queen (Jamaica) [2016] UK PC 7. See also page 42 of this issue.